Posted on July 28, 2016 in Uncategorized

Pacific Presences Visiting Research Fellow Anna-Karina Hermkens writes about her work on barkcloth for the project in relation to the recent Festival of Pacific Arts, held in Guam (22 May-3 June), and an extraordinary exhibition of reinterpreted Tongan barkcloth at the National Gallery of Victoria, Australia (10 June-11 September 2016). My research project for the Pacific Presences Project aims to describe and compare barkcloth (tapa) collected in ‘Melanesia’ and ‘Polynesia’ in the collection of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, detail and analyse its particular colonial representations, and relate these to current performances and discussions in Oceania about making barkcloth cultural heritage.

As part of this project, I was fortunate to be able to attend the Festival of Pacific Arts, held in Guam (Mariana Islands). The Festival of Pacific Arts, also called FESTPAC, is a travelling festival hosted every four years by a different country in the Pacific. The Festival was envisaged by the Conference of the South Pacific Commission (now the Secretariat of the Pacific Community, SPC) in an attempt to combat the erosion of traditional customary practices. Since 1972, delegations from 27 Pacific Island Nations and Territories have come together to share and exchange their cultures at each Pacific Arts Festival. The Festival “is recognized as a major regional cultural event, and is the largest gathering in which Pacific peoples unite to enhance their respect and appreciation of one another”.[i]

In Guam, which was the 12th country to host the festival, around 2,500 performers, artists and cultural practitioners showed their skills in canoe-faring, performed dances, music and poems, showcased their films and artworks, and sold and demonstrated ‘traditional’ arts and crafts, including barkcloth.

The Tongan delegation performing at FESTPAC, wearing layers of ngatu (barkcloth).

The pavilion of the Tongan delegation at FESTPAC with fine mats and ngatu.

Barkcloth, often referred to as tapa, but known as ngatu in Tonga, masi in Fiji and kapa in Hawaii, amongst others, is known and used across Oceania. In many Pacific Islands, people have been making barkcloth from the paper mulberry tree, but it is also being made from the inner-bark of Ficus trees. The cloths, which vary from small strips of loincloth to more than twenty metres-long pieces of cloth, are intimately interwoven with past and present socialities across Oceania. They have been used to decorate, wrap, cover, protect and carry the human body, as exchange valuables and commodities, in land claims, and as indexes and embodiments of ancestral power. It therefore comes to no surprise that tapa was very much part of the Festival of the Pacific Arts. Not only was it worn by many delegates during their dance performances, it was also sold as both raw material and decorated cloth, as framed paintings and as sculptures. Among those buying tapa were not just tourists and festival visitors. Pacific delegates exchanged pieces with each other and bought each others work. For example, Rapanui delegates, who value tapa immensely as it is part of their ‘lost’ cultural heritage which they try to reclaim, but also because mulberry trees are scarce on Rapanui, bought large pieces of undecorated white tapa from Tongan delegates, as well as a large piece of decorated Fijian tapa.

For the Samoan, Fijian, Tongan and Rapanui tapa makers I spoke with during the Festival, tapa is about their culture. As Fijian Talei Manara stated, “everything we do, we must wear masi (tapa)!” But it is also seen as something that connects Pacific Island societies with each other and the wider world. “Masi will send you around the world”, said masi maker Selai Buasala, who teaches her daughters how to make and design (paint) masi, just as her mother taught her. It opens up different pathways, enabling Pacific islanders, and especially local women, to travel in order to promote and sell their tapa work. But essentially, it is “about our place in the world”, as Moana Eisele from Hawaii expressed, about what it means to be Hawaiian, Tongan, Samoan, or Fijian.

Moana Eisele making Hawaiian kapa (tapa).

This capacity of barkcloth to reach out and at the same time create regional and local belongings and identity, has been taken up and pushed further by New Zealand-Aotearoa based printmaker and painter Robin White and Tongan artist Ruha Fifita in their collaborative project ‘Siu I Moana: Reaching Across the Ocean’, which is on display in the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne (Australia). In their vision, their collaborative series of re-interpreted Tongan barkcloth (ngatu) form a pathway, not only for Pacific Islanders, but also for humanity at large to come together and create connections. Importantly, White and Fifita’s project is part of the largest exhibition of contemporary Pacific art ever to be held in Australia this far. Stereotypically being classified as craft instead of art, Pacific arts such as painted barkcloth have predominantly been displayed in ethnographic museums. And while receiving recognition for their work in New Zealand and Europe, Pacific artists and their work have been structurally underrepresented in the Australian museum context. As such, White and Fifita’s ngatu has already proved to be a pathway for both Pacific arts and artists to enter the Australian gallery and art market and to finally receive recognition by one of Australia’s leading national galleries.

White’s and Fifita’s choice for barkcloth as their medium comes perhaps as no surprise as it is inherently part of Ruha’s Tongan ‘roots’ and referred to by White as “the DNA of the Pacific”. White and Ruha have imbued Tongan ngatu, which is traditionally used as ceremonial gift in weddings and funerals, as garment, and part of royal inaugurations and rituals, not just with artistic skill and significance, but also with new spiritual meaning.

Three of the eight ngatu (painted barkcloth) composed floating in a huge white cube, with the center piece (titled Seen along the avenue) stretching out towards the entrance, inviting the audience to enter the room and follow the halakafa – at once a pathway and, traditionally, a place for tying rope ‒ that runs through the middle of the ngatu and which leads to the sacred and the spiritual (Mt Carmel).

For White and Fifita, the collaborative creative process of working with the earthly materiality, timbre and temporality of barkcloth and traditional dyes, engendered a sense of wholeness. This wholeness has, as they hope, not only fulfilled themselves, but also imbued their ngatu with a significance that transcends the mere artistic. The layers of soft white ngatu, painstakingly painted with both old and new metaphorical and symbolic designs, are envisioned to wrap and bring people together, regardless of gender, age and ethnicity.[i] Siu I Moana is therefore indeed reaching across the Ocean, just like the Festival of Pacific Arts does. It connects people in the Pacific (Tonga and New Zealand) and in the Australian Pacific diaspora, but it also reaches out to all of humanity in the hope of engendering uplifting experiences of community, hope and renewal.[ii]

I hope that my project for the Pacific Presences Project generates similar forms of connectedness by connecting historical museum collections with present-day tapa makers, creating new understandings and valuations of tapa past and present.

[i] Ryan, Judith 2016. ‘Siu i Moana: Reaching across the Ocean.’ Essay. https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/siu-i-moana-reaching-across-the-ocean/

[ii] Interview with Robin White and Ruha Fifita, Melbourne 12 June 2016.

[i] https://festpac.visitguam.com/visiting-the-festival/about-the-festival

Anna-Karina Hermkens 2016

Posted on July 20, 2016 in Uncategorized

In February and March 2016 conservator Rachel Howie undertook an internship with the project, here she reflects on the work she did:

For two months I had the opportunity to research and conserve some amazing objects from the collection of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA), Cambridge. These included a porcupine fish helmet, and coconut fibre armour consisting of a cuirass, sleeves and overall-style trousers. The aim of the project was to conserve and mount the objects for display in a micro gallery exhibition at MAA in 2017, and for loan to the Royal Academy in 2018. In addition I had to research the materials, manufacture and use of the armour and helmet. This included looking at comparable examples in various UK institutions. In this blog post I will concentrate on the conservation.

Coconut fibre armour Z 7034

The cuirass, sleeves and trousers are all made from coconut fibre with human hair used for the decoration. The armour was generally in a good, stable condition, but covered in a layer of museum dirt. All three pieces were cleaned with brush vacuuming and then with groomstick (natural rubber). A small number of the human hair bindings on the cuirass required stabilisation, this was done using tinted Japanese tissue to secure the binding with a wheat starch paste: 4% methylcellulose 50:50 adhesive.

The trousers had a number of holes along the sides and one on the chest. These were secured with dyed nylon netting on the outside and the large hole on the side was also secured on the inside with dyed silk. This prevents the holes from increasing in size and also stops the mannequin from being visible through the hole while on display. Both the sleeves and trousers had deep creases along the edge from being stored flat. These were relaxed using local humidification with damp blotting paper and sympatex (a waterproof, water vapour-permeable membrane). Sympatex membrane brings the applied moisture in gaseous form to the surface of the object without the object actually coming into direct contact with the liquid.

Porcupine fish helmet Z 7035.

An impressive feature of the Kiribati armour is the helmet made from a hollowed out and dried porcupine fish. The helmet was created by hunting a porcupine fish while it is fully inflated and then burying it in the sand until it is dried out. The head is then removed and the skin is expanded in order to accommodate the head of the wearer. Ear guards were cut from the fish’s body.

Some helmets are composed of just the dried skin of the fish (like the MAA example), while some examples are reinforced with an internal coconut fibre helmet (see British Museum Oc1904,0621.28) and others are lined with plaited pandanus strips around the edges (see BM Oc1887,0201.54). The are several types of porcupine fish used, our helmet is from the Diodontidae family, most likely the Diodon hystrix as this was commonly used, however this cannot be confirmed for certain.

Before conservation

When the helmet arrived at the conservation lab it was unfortunately in a poor state. The ear guards were misshapen and bent inwards into the cavity of the helmet. They were both very dry and rigid, and each one had a tear along the bend. In addition there was also a number of broken barbs.

After conservation

The helmet was surface cleaned using a soft brush and conservation vacuum. This was done with incredible care as the surface of the skin was covered in sand, which could have been due to the manufacturing process, so I wanted to leave this in place. Luckily the sand was attached quite securely to the surface. The broken barbs were repaired using 20% Mowilith 50 (polyvinyl acetate) in 50:50 Industrial Denatured Alcohol: acetone, as this is a strong adhesive and tacky, but allows the retention of flexibility.

The main issue was the misshapen guards. There are a number of ways to reshape materials from localised humidification using sympatex sandwiches, to humidifying the whole object by creating a humidity chamber. As it was only the flaps that required reshaping I decided to use localised humidification using a preservation pencil connected to an ultrasonic humidifier. When this was complete I now had access to the reverse of the tears so was able to stabilise these by attaching a backing of Japanese tissue (Tosa tengujo) with 2% Methylcellulose in deionised water.

Now that the objects have been cleaned and stabilised, they are ready to be mounted for the exhibition. Due to the fragile nature of the materials this will take place next year just before the exhibition opens in April 2017. Thank you to the Pacific Presences team for providing me with the opportunity to research and work on such unusual and interesting objects.

Rachel Howie 2016

Posted on July 14, 2016 in Uncategorized

Pacific Presences Affiliated Researcher Areta Wilkinson writes on her most recent work for the project in Guam in May 2016:

Thank you to the Pacific Presences project for supporting my participation at Mo’na Our Pasts Before Us, 22nd Pacific Histories Association Conference in Guam, Mariana Islands. Over the last few years I have been fortunate to join Pacific Presences photographer Mark Adams and other project staff on research trips. As an Affiliated Researcher, the project has also supported my own artistic inquiry of taonga Māori (Māori customary objects) held in museum stores in England and Germany.

Mark Adams, Areta Wilkinson and Julie Adams in the dark room. Acknowledgements: Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin and Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde of Munich

In the dark room. Acknowledgements: Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin and Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde of Munich

Under the Pacific Presences project Mark and I have developed an ethical conceptual collaboration that is a marriage of both our creative practices and more. We have produced new artworks that respond to and acknowledge taonga Māori in museums abroad. This new body of work feels highly significant to us because we would not have produced this work on our own, it requires both our cultural genealogies (that relate to the object) in order to do so. Thus far we have only exhibited the resulting artworks in New Zealand, Pacific Presences staff knew what we were up to but had not seen the fruits of our (and their) labour. The 22nd PHA conference was a fantastic opportunity to share our contemporary artistic outcomes responding to Oceanic art and European museums with our own Pacific Presences crew as well as conference goers.

24.7.2015 Silver Bromide Photogram. Z6469 Cheviot Hill. Collections of Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge, UK. Silver bromide fibre based paper Areta Wilkinson and Mark Adams 2015

Presenting alongside Nicholas Thomas, Julie Adams, Ali Clark, Lucie Carreau, Alana Jelinek, Maia Nuku and others under the diverse Pacific Presences project umbrella was certainly a highlight. Papers spanned three sessions over which I caught up on our team’s research developments and objectives. I felt this was a concerted effort by MAA and associates to reach out to scholars working in the Pacific, prior to connecting with indigenous artists at the Pacific Arts Festival that followed. Community books of Oceanic collection material held at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge and in other museums in Europe and New Zealand were created for the purpose of connecting communities with objects. I am pleased to hear these booklets came into their own when researchers went on to visit villages in the islands of Kiribati, Kanaky, and the Solomons.

It has been several weeks now since PHA but two lasting impressions have stayed with me since leaving Guam. Firstly, I noticed and appreciated indigenous scholars placing themselves in their research. Their relationship or cultural position was not presumed but up front and implicated. Māori academic Linda Tuhiwai Smith has contributed to my critical thinking about this through her articulation of Māori methodologies. In Māori centred frameworks, Māori are positioned as the collective stakeholders of their own knowledge, Māori take an active role in knowledge production and who benefits (Tuhiwai Smith 1999). In a cross-cultural context indigenous research as Localised Critical Theory also benefits the indigenous community being researched (Denzin, Lincoln, & Tuhiwai Smith 2008, p. 9). Politically I have occupied myself with Kaupapa Māori principals (Māori Critical Theory) over the last few years, so I found it confusing at PHA when conference presenters did not disclose their methodology behind engaging with cultural knowledge that obviously was not their own. Papers that discussed a cultural form without revealing their relationships to the culture fell short for me. This sort of inquiry is not robust enough anymore.

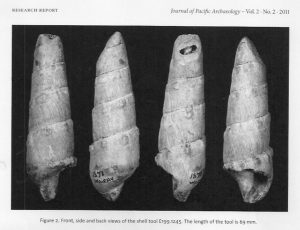

Secondly, I was made aware of my own short comings then had a Te Ao Marama “lights on” moment. In a discussion following panel presentations about Māori History, Vincente Diaz in his questioning of the panel seemed to remind our assembled collective to look for whakapapa connections beyond Polynesia, into Melanesia and Micronesia. To seek and find relationships is also a valued convention within our Māori rituals of encounter. As manuhiri, being a visitor, on the indigenous island Guahan I felt I could have improved on my own relating into the Pacific beyond Aotearoa New Zealand. I didn’t do this in my paper but during this session’s discussion a cog turned for me. Suddenly I had a better understanding of the presence of a photogram artwork that Mark and I had made, taken from a shell tool from the Pacific found in the site of Wairau Bar, Te Waipounamu South Island. Here was my mnemonic for Diaz’s message, my link to East Polynesia and beyond was under my nose all the time. But I had to be in a Pacific context, confronted by Pacific peoples to work it out.

The shell tool from Wairau Bar, E199.1245. Collection of Canterbury Museum, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Post PHA, Mark and I very recently accompanied Lucie Carreau with her whānau on her research trip to Norfolk Island. This time I was proactive to reach across into the Pacific to make connections. With the assistance of Norfolk Island Museum director Janelle Blucher Director and local artist Kerry Robertson we initiated an evening with locals to share our research interests. Face to face kanohi ki te kanohi it was a wonderful meet and greet opportunity that we all appreciated. Further contacts in the days remaining made it clear another trip would be warranted and we would all be welcomed back.

No reira, these research trips continue to have a positive impact on the development of my thinking and practice. Hei kona ma, na te ropū whakahaere, until we meet again.

Dr Areta Wilkinson, NZ (Ngāi Tahu)