Posted on June 26, 2017 in Uncategorized

Over three weeks in April 2017, Pauline Reynolds, a visiting researcher with Pacific Presences, various museums in order to study tapa made by my foremothers. This began with attending the second day of the Museum Ethnographers Group conference in Glasgow, a fitting way to begin my collaboration with Pacific Presences and contextualise my visit.

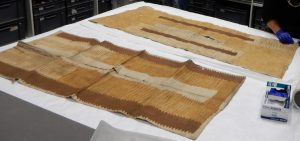

The first museum visit was to King’s Museum with Lucie Carreau where a beautiful example of a Pitcairn tiputa (something like a poncho) is held. I’m particularly attached to one of these examples, because we know the name of the maker, it shows signs of wear and tear, and it has become familiar to me, like an old friend. The curator Louise Wilkie had discovered another two cloths – one a tiputa, and another a length of undecorated white tapa, which made the day exceptionally successful. The tiputa at the top of the photo here was made by Dinah Adams, the daughter of Vahineatua and mutineer John Adams

Photo by Lucie of refs ABDUA 4007 and 4008

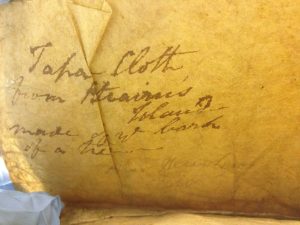

In Glasgow we visited the Centre for Textile Conservation where the research project ‘Situating Pacific Barkcloth Production in Time and Place’ is operating, and viewed examples of Pitcairn tapa from the Kew collections and the conservation techniques used in their care, and spoke extensively with the conservation team including Andy Mills, Frances Lenndard, Misa Tamura and Beth. This was followed by a visit to the Glasgow Museum Resource Centre guided by Ed Johnson and Pat Allan, where we were able to observe a range of different coloured cloths – one dyed a stunning rich yellow dye, another a dirt brown, another cloth was so fine it resembles a loose gauze.

Photo by Lucie of ref 79-42 hj

I had met Michaela Appel at the Made in Oceania conference in Cologne in 2013, and she was sure that the Five Continents Museum in Munich had a tiputa similar to the King’s Museum example. Sure enough, when I visited with Erna Lilje, I recognised the unmistakable patterning that is unique to Pitcairn tiputa – it is a fine example. While we were there, Hilke Thode-Arora and Michaela showed us a large range of beautiful Polynesian tapa, part of an extensive and fabulous collection.

MUNICH photo by Pauline ref. Inv. Nr. 131

One of the great strengths of participating in Pacific Presences from my point of view is being able to engage in worthwhile and inspiring exchanges with the Pacific Presences team, in particular Lucie and Erna, while observing Pitcairn and Tahitian tapa. At the British Museum’s Blythe House stores, we saw a number of tapa that I had seen before, but observing them with Lucie Carreau, Julie Adams, Jill Hassell, and my daughter, allowed for vigorous discussion around a range of issues: colour, dye, size, technique, use, the effects of conservation … as well as exacting observations – the width of beater grooves used and other techniques. We required two full days at the British Museum stores, and could easily have stayed another, examining the wide range of cloths.

British Museum group photo by Pauline

Throughout my research I have found it most helpful to ask myself the following questions when collecting data about tapa and related objects:

What is it, what are its qualities?

Who made it? Who gave it?

When was it gifted or collected?

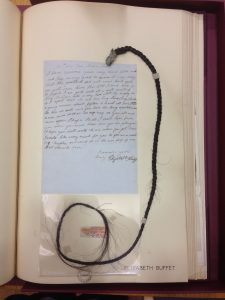

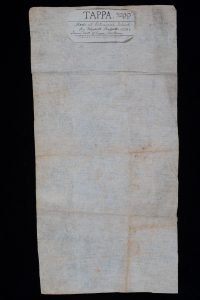

It is sometimes possible to build a picture of a Pitcairn woman and her relationships by the gifts she gave. Hannah, Dinah’s sister (who made the Aberdeen tiputa in the photo above), wrote to Rear Admiral Lowther who had visited Pitcairn in the 1850s, expressing herself eloquently in both Tahitian (her mother’s language) and English, an important revelation showing that Tahitian was still fluently spoken on the island at that time. This letter, along with another written by Hannah’s daughter Elizabeth Buffett, is located at the Centre for Anthropology in the British Museum. Elizabeth also gifted a finely made cloth to a visitor to Pitcairn in 1850, of which a small section is today at Hastings Museum.

British Museum Library of Anthropology photo of Elizabeth Buffett’s letter to Lowther and a lock of her hair

HASTINGS MUSEUM tapa, photo © Hastings Museum & Art Gallery

There were a number of surprises in the collections we visited. Newly discovered cloths in various locations could possibly mean that my database of Pitcairn tapa will be forever expanding. Incorporating these items into my expanding documentation has allowed my profiling of the Pitcairn women to expand and fill in gaps I thought would always remain a mystery.

Finally, a visit to Pitt Rivers with Nicholas Crowe and Faye Belsey was impressive, discovering another “new” tapa, observing conservation techniques, and a fine collection of archaeological objects from Pitcairn and around the world, while time in Cambridge allowed me to visit a number of important items at the MAA, give an informal talk about my visit, and learn from the wonderful team of the Pacific Presences Project.

These tapa act as vessels, transporting me back through time, where (if I’m lucky) I might catch the scent of the air at the time of its production, imagine the maker’s mindset, marvel at her skills, and puzzle over her choices. This is a personal journey of discovery and genealogy, but also one that will eventually benefit all descendants of these amazing women. I was struck by the care and attention, and attachment that curatorial teams hold for each of these tapa: which is heart-warming considering the Pitcairn tapa are genealogical markers for my people. I benefited from the robust conversations around tapa during my research trip with all of these curators, and the Pacific Presences team.

Pauline Reynolds, 2017.

Posted on June 4, 2017 in Uncategorized

Katharina Wilhelmina Haslwanter is a PhD student from Zurich University and an affiliated researcher of the Pacific Presences project. In the following two blogs, she presents some of her recent research findings on the Wollaston collection, and therewith gives insight into the early history of MAA.

In summer 2015 and January 2016, I was researching the western New Guinea[1] collection from Alexander Frederick Richmond Wollaston at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA) as part of a Doc.Mobility research fellowship from the Swiss National Science Foundation. During my current internship with the Pacific Presences project I decided to take up my research on this collection again, trying to solve the puzzles surrounding the numbering of this collection.

Dr Elisabeth Blake, who kindly helped me during my research in 2015 / 2016, has already given a fascinating insight into the 1912-1913 Wollaston expedition in a previous blog post. I would like to complement her account with additional information on Wollaston and his expeditions as an introduction.

Alexander (Sandy) Frederick Richmond Wollaston (1875-1930)

Sandy Wollaston, a British ornithologist, medical doctor, botanist and explorer, participated in two expeditions to Dutch New Guinea. Both expeditions moved from the south coast into the island’s interior with two aims: to collect scientific specimens and to reach the snow-covered mountains of the Nassau Range (now Sudirman Range). The first expedition was undertaken by the British Ornithologists’ Union in 1910 and 1911. While bringing back diverse collections, they did not get further than 40 km inland let alone reach the mountains, as the expedition was ‘poorly planned and deliberately misdirected by the Dutch authorities’[2] towards the Mimika river.

Disappointed by this defeat, Wollaston decided to try it a second time following another river route. With financial support from the British Ornithologists’ Union and private benefactors, Wollaston himself led a second expedition to western New Guinea in 1912-1913. This time they followed the Utakwa (today Otakwa) and Setakwa Rivers from the south coast up to the Tsingarong and Bandarong Rivers, and finally managed to reach the base of the glacier, which covered the higher region of the mountain range. However, they could not get further, because they didn’t have the right equipment nor the necessary experience to tackle the glacier.[3]

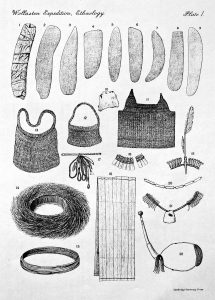

Nevertheless, the members of the two British expeditions collected important natural history specimens and ethnographic material and documented their encounters with the Papuans in photographs and in notes. The ethnographic collection is diverse, ranging from clothes and body decorations, tools and weapons to musical instruments and carvings, as the following two images demonstrate.

Headdress made of 99 humeri (upper arm bones) of a phalanger (a marsupial) from the Amungme (prefix+H&L 1914.231.216).

Wollaston donated the biggest part of his object collection to the then called Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (MAE, the predecessor of today’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, MAA), namely 231 entries[4] representing 408 objects.[5] A further part of his collection (184 entries) is at the British Museum. Of the 231 entries at MAA, two third come from the Kamoro people which live in the lowlands at the south coast of western New Guinea. 79 entries come from the mountain areas, namely from the Tsinga valley Amungme and a group of people who probably were Ekari- or Moni-speaking[6] to which Wollaston referred to as ‘Tapiro’.

Already during my research on the Wollaston collection in summer 2015, I was puzzled by the many different sets of numbers associated with the objects. One object could bear up to four different numbers –as can be seen in the image of the prow ornament above – which made the search for an object entry on the digital database quite challenging. Moreover, in most cases there were at least two digital records for a single object. At the time, my research focused on the objects themselves –their use, origin and composition – not on their museum history. I remained, however, interested in understanding what generated multiple numbers and digital duplications. As part of the Pacific Presences internship, I decided to investigate the way in which the Museum handled the Wollaston collection once it entered its walls. Here, I would like to share what I have found so far.

Various sets of numbers

After his return from the second expedition, Wollaston loaned his collection[7] to the MAE, where the honorary keeper Alfred Cort Haddon and his assistant John Willoughby Layard undertook comprehensive research on it, comparing it with other specimens from the same region of origin, in the UK as well as at the Rijksmuseum Leiden in the Netherlands. The purpose of their research was the compilation of the Report on the Ethnographic Collection from the Utakwa river made by A.F.R. Wollaston, which was published in 1916 as part of the larger British Ornithologists’ Union’s Report on the Collections made by the British Ornithologists’ Union Expedition and the Wollaston Expedition in Dutch New Guinea 1910-13. Their report gives a detailed description of the object’s composition as well as information on their use and value as it was known at the time, and included eight plates with astonishingly accurate sketches of the objects, as can be seen in the example below. For their report, Haddon and Layard numbered the objects present from 1 to 257. This is one set of numbers[8] associated with the collection (which I will refer to as H&L numbers), usually found printed on square labels adhered to the objects.

Photograph of Plate I in Haddon and Layard’s ‘Report on the Ethnographic Collection from the Utakwa river made by A.F.R. Wollaston’ (Doc.58, MAA Archive).

When Haddon and Layard finished their research for the report, 105 objects were returned to Wollaston in March 1914. The rest of the collection remained at the MAE as a gift from A.F.R. Wollaston. It was then accessioned into the Museum’s Register, assigned with the only recently introduced three-part numbering system, which is a combination of the accession year (1914), the number of the collection (231) and a suffix for every individual object or object group. As there were 187 objects or object groups respectively, the Accession Register numbers for the Wollaston collection are therefore 1914.231.1 to 1914.231.187. It is important to mention that in the case of the Wollaston collection, the collection was first numbered for the Annual Report, where it has the numbers 1914.371.1 to 1914.371.187 (note the different collection number between the dots. This is another set of numbers.). Only after this, the collection was accessioned into the Accession Register, as cut out copies of the Annual Report glued into the Accession Register indicate.

Most of the objects however do neither bare the Accession Register number (which would have been and still is the rule), nor the Annual Report number, but a combination of the accession year, the collection number and as a suffix the numbers used by Haddon and Layard in their report, leading to a range of numbers between 1914.231.1 to 1914.231.257 (which I will refer to as prefix+H&L numbers).[9] This of course made it difficult to link the object to its corresponding Register number.

Let me illustrate this with an example. While the Register number for the object below – a string bag with a protective shield and a sliver of bone from the Amungme – is 1914.231.34, the object itself is inscribed with the prefix+H&L number 1914.231.219.

So far, I have not found any document that would explain why on the objects the prefix+H&L numbers were used instead of the official MAE Register numbers, which would have been the rule.

One reason for this might be linked to the fact that a big part of the Wollaston collection was on display[10]. If the Museum staff would have put the new Register numbers with the objects, the connection with the H&L report numbers and therewith the vast knowledge on the objects documented in the report would have been lost for the visitors. To make clear to which collection the objects belong, it might have been decided to add the accession year and the collection number to the objects as well. This could have led to the combination found on the object. However, this is only one possible explanation, and proof for it is needed.

I would like to close this blog entry by pointing out, that while our research privileges the physical objects –their use and construction, their origins and histories, their meaning to the people who made and used them and their descendants, as well as to people who look at them and work with them in museums now, and the many other aspects object research can involve – it is also part of our museum duty to retrace the journeys that bring objects to museums and to consider how they are processed within these institutions. It provides an important insight into the practice of museum work and the methods implemented in museums historically. Even if it might sound rather tedious to some, it is an exciting and important part of museum work, which can be highly satisfying, when one encounters a missing piece of the puzzle and suddenly the picture becomes clearer.

Katharina Wilhelmina Haslwanter, 2017

References

[1] With western New Guinea I am referring to the western half of the Island New Guinea, which is currently a part of Indonesia and organised into two provinces, Papua and Papua Barat (West Papua).

[2] Ballard, Chris (2001). A.F.R. Wollaston and the ‘Utakwa River Mountain Papuan’ Skulls. In: The Journal of Pacific History, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Jun. 2001), pp. 117-126: p. 117.

[3] Klein, Willem Carel (1954). Nieuw Guinea. De ontwikkeling op economisch, sociaal en cultureel gebied, in Nederlands en Australisch Nieuw Guinea, Vol. III. ’s-Gravenhage: Staatsdrukkerij- en uitgeverijbedrijf: p. 73-74.

[4] With ‘entry’ I mean an entry in the Accession Register. However, one such entry can comprise of more than one object, for example the entry 1914.231.35 is a jaw’s harp and its case, and therefore two objects.

[5] The biggest part of the collection was given in 1914, two smaller additions reached the Museum in 1924 and 1925.

[6] Cf. Ballard, Chris (2001). The British Expeditions to Dutch New Guinea (1909-13). In: Ballard Chris, Anton Ploeg and Steven Vink (eds.). Race to the Snow. Photography and the exploration of Dutch New Guinea, 1907-1936. Amsterdam: Royal Tropical Institute, pp. 27-34: p. 30.

[7] It was mainly his collection from the second expedition, but included some specimens from the first expedition.

[8] It was not the first set, though, as Wollaston had himself numbered the collection, as a little notebook in the British Museum archive reveals. And it was not the last set, as the collection has another number in the Accession Register (1914.231.1 to 187) and the Annual Report (1914.371.1 to 187). Finally, some singular objects bear an additional ‘Z Number’, which had been used in different ways over time, e.g. as a temporary number to objects that could not be correlated to a number in the Accession Register. This means that there are up to six numbers associated with some objects in the Wollaston collection.

[9] This range of numbers is of course incomplete, as 105 of the objects bearing H&L numbers have been given back to Wollaston.

[10] The Annual Report for the year 1928 notes that the Honorary Keeper of the New Guinea collection, Dr Haddon, ‘overhauled all the ethnographical specimens from Netherlands New Guinea, and installed as many as possible in the Andrews Gallery. The collections from the Utakwa River given by Dr Wollaston can now be conveniently studied.” The collection remained on display – with a brief interruption during the Second World War – until the refurbishment of the Museum in the 1980s.