Posted on July 12, 2017 in Uncategorized

In a previous blog, I described the different numbers associated with the collection of Alexander (Sandy) Frederick Richmond Wollaston, and how these many sets of numbers might have come about. The most problematic aspect is that most objects are not inscribed with their Accession Register number, which was standard practice, but instead with a number that comprises of the year of accession, the collection number and a suffix based on the numbers used by Alfred Cort Haddon and John Willoughby Layard in their Report on the Wollaston collection.[1] This has continuously created confusion for all researchers willing to engage with the Wollaston collection. Quite a few attempts were made over the years to understand this situation. If one started with the catalogue cards, one was warned right away by an inscription on one of the cover cards to the Wollaston collection: ‘Part, at least, of Wollaston collection seems to have been accessioned twice, as these nos. overlap. Beware + good luck!’

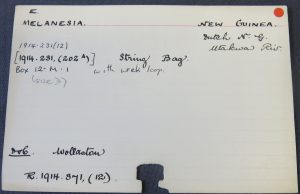

The first documented effort to make sense of the different numbers on the objects[2] and in the Accession Register was undertaken in the late 1970s by Mrs Joan Cunning, a retired librarian from Melbourne, Victoria, and Honorary Keeper of Records between 1975 and 1980. In these five years, she was ‘checking and sorting the catalogue cards referring to specimens acquired between 1883 and 1919’ and ‘matched the accession lists with the entries in the annual reports’.[3] Even though the majority of the catalogue cards give the prefix+H&L2 number at the top and the Annual Report number[4] at the bottom, as can be seen in the example below, Mrs Cunning could not relate the prefix+H&L numbers (which were also inscribed on the objects) to anything else. Moreover, there were gaps in the series, which made it even harder for her to understand. A note in the Accession Register 9 (p. 57) in Mrs Cunning’s hand explains that ‘[T]his collection has been labelled with a curious collection of numbers not corresponding to the register or the Annual Report.’ It is thus likely that Mrs Cunning did not have the Haddon and Layard report to hand,[5] when working on the Wollaston collection.

Nevertheless, she added the Accession Register number just above the prefix+H&L numbers on top of most of the catalogue cards (cf. image above). Additionally, she noted in pencil the specific Accession Register number on top of every object in the Accession Register, as can be seen in the image below.

Extract from the Accession Register number 9, page 57, showing the specific accession number written in pencil on top of the objects.

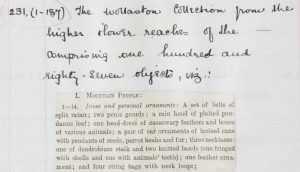

After more than 20 years, the next important step in unravelling the riddles of the Wollaston collection was undertaken by Karen Jacobs, now Lecturer in the Arts of the Pacific at the Sainsbury Research Unit, University of East Anglia, who researched the Wollaston collection for her PhD on Kamoro Art and Collecting in 2004. In the meantime, the collection had been taken off display, and had been stored in numerous different boxes and on racks in the back rooms of the museum. Having conducted research at the Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde in Leiden, Netherlands[1], Karen Jacobs found a copy of Haddon and Layard’s report at the Library there and brought a working copy of it with her to Cambridge. Therewith she was able to compare the objects with the descriptions and sketches in the report, reconnect the Accession Register number with the prefix+H&L number on the objects and verify the connections made earlier by Mrs Cunning. In addition, she wrote new labels which she attached to the objects found, and compiled an important report on the collection, including a vast amount of information from Haddon and Layard’s report and other sources.[2]

However, there remained some oddities which couldn’t be explained – why was it not possible for Joan Cunning, Karen Jacobs and myself to correlate some of the objects we found during our research with any of the Accession Register numbers, even though these objects were obviously part of Wollaston’s collection, as the typical labels proved.

So far, six such objects could be located. They are mentioned in Haddon and Layard’s report and show the typical square adhesive label with the H&L number. After checking the list of objects that were returned to Wollaston it seems indeed that these objects were part of the gift to the museum. But why are they then not mentioned in the Annual Report or in the Accession register?

Clues in the paper archive

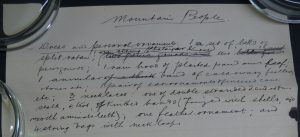

In museum (and probably many other) archives, sometimes notes survive, which in regular circumstances probably would have been scrapped. Two such examples, one handwritten and one typewritten list, were found in an envelope labelled ‘Combined lists (roughs) used for compiling the list of Wollaston Collection (Utakwa River) D.N.Guinea, for 1914 list in Annual Report’. Looking through these lists, I found some of these six objects.

The first example can be seen in the image below. It is ‘one strung phalanger humeri’[3] on the ‘Mountain People’ (Amungme) list, which was written in between the lines and therefore could easily be overlooked. This head dress of upper arm bones of a marsupial is depicted and described in Haddon and Layard’s report as the number 216. The object found in the stores does indeed match the sketch in the report and bears the prefix+H&L number 1914.231.216. However, it was never recorded in the Annual Report, and as the Annual Report was used to create the entries in the Accession Register, it was not given an Accession Register number.

Similarly, a ‘rain hood pandanus leaf’ (prefix+H&L number 1914.231.141) was written in the top right corner of the ‘Coast People’ (Kamoro) handwritten list, but was missed during the transfer into the Annual Report.

Two other objects, namely a string that is holding a penis gourd (H&L number 207) and a tassel which would have been attached to the gourd (H&L number 208), are not mentioned in the Annual Report. They seem to have been sacrificed to the necessity ‘to abbreviate as far as possible the description of specimens in the Accession List’, as stated in the Annual Report for the year 1914, page 4. While they have been described and depicted as one set in Haddon and Layard’s report (see below), in the handwritten list (above) it reads ‘two penis gourds and two belts for penis gourds’. The words ‘two penis gourds and’ and ‘belts for’ were crossed out with pencil, leaving the words ‘… two … penis gourds’. Even if the string and the tassel are not mentioned in the Annual Report, it seems likely, that the abbreviation ‘penis gourd’ would refer to the whole set, and not just the gourd, especially, as all three objects remained at the MAA.

Extract from Haddon and Layard’s ‘Report on the Ethnographic Collection from the Utakwa river made by A.F.R. Wollaston’ (1916: 8).

Finally, there are two canoe prow ornaments (1914.231.242 and 1914.231.243) without an Accession Register number. The lists describe the prow ornaments in plural, whereas the Annual Report only mentions one prow ornament. Mrs Cunning, who came across one of them[1] in the 1970s and was unable to find a corresponding Accession Register number, decided to add this object (H&L number 242) to the Wollaston collection and to give it the next following Accession Register number: 1914.231.188. Admittedly quite a creative solution as the collection is everywhere noted as comprising of 187 numbers, but also a clever one, as it allowed the object to be identified as part of the Wollaston collection but without colliding with numbers already assigned to objects, as in the case of the rain hood with the prefix+H&L number 1914.231.141 to which an arrow exists with the Accession Register number 1914.231.141.

A possible hint to the reasons for these omissions in the Annual Report might be between the lines of the Annual Report for the year 1914 (page 4), where one can read: ‘WORK DONE. Lists of Accessions numbering over three thousand objects received during the four years 1910 – 1913, have been compiled by the Curator and issued with the belated annual reports for 1912 and 1913. […] Lack of show-cases has retarded work. It becomes more and more difficult to supervise the specimens and secure them from damage by moth etc., so long as the bulk of the collections remain packed up in boxes.’ If one thinks about compiling lists for the Annual Report under these circumstances, it seems understandable that some of the objects, although present at the museum, might have slipped the close attention of the Museum personnel compiling the lists.

Having found these explanations, I went back to the excel-file I compiled as part of my research, which I have organised according to the Haddon and Layard numbers. I checked how many other objects from the collections were not returned to Wollaston but are not mentioned in the Annual Report either and therefore could / should still be at the museum. I found another three.

The hunt is on!

Katharina Wilhelmina Haslwanter

[1] An image of this object can be found in the previous blog on the history of the Wollaston collection.

[1] Since 2005 the museum is called Museum Volkenkunde and since 2013 it is part of the museum group Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen (National museum for World cultures).

[2] Jacobs, Karen (2004). Report: analysis of the collection assembled by A.F.R. Wollaston in Dutch New Guinea (1910- 13). Unpublished Crowther-Beynon Fond report on the Amungme objects in the Wollaston collection.

Jacobs, Karen (2004). ‘Coast People’ or the Kamoro collection assembled by A.F.R. Wollaston in the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge University. Unpublished Crowther-Beynon Fond report on the Kamoro objects in the Wollaston collection.

[3] An image of this object can be found in the previous blog on the history of the Wollaston collection.

[1] Haddon, Alfred C. and Layard, John W. (1916). Report on the Ethnographic Collection from the Utakwa river made by A.F.R. Wollaston. In: British Ornithologists’ Union. Report on the Collections made by the British Ornithologists’ Union Expedition and the Wollaston Expedition in Dutch New Guinea 1910- 13, 2 vols. Francis Edwards, London, 1916, Vol. II, part 19.

[2] The number inscribed on most objects comprises of the accession year, the collection number and the Haddon and Layard suffixes. I will refer to this number as prefix+H&L number.

[3] Cf. the Annual Reports of these years, for the quotes esp. 1974-75 page 2 and 1977-78 page 5 as well as the pencil entry in the Accession Register 9, page 57.

[4] Accession Register number and Annual Report number do only differ from each other in the collection number in the middle, but prefix and suffix are the same. The same object would be 1914.371.33 in the Annual Report, but 1914.231.33 in the Accession Register.

[5] There is a copy of Haddon and Layard’s Report in the archive of the MAA (Doc.58), but it is unclear since when. However, even if it was already there when Mrs. Cunning was working on the collection, she might not have known about it or did not find it. Even though the archive was first sorted in 1967 by the then Assistant Curator Marilyn Strathern, Haddon and Layard’s Report got registered as Doc.58 only in 2006 by Imogen Gunn.