Posted on April 3, 2018 in Solomon Islands, Uncategorized

In this blog entry Pacific Presences intern Hannah Eastham describes a short piece of work on the collection of Toshio Asaeda at the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka, Japan.

Having spent the last 2 years living in Osaka to develop a PhD project on the photographs of Japan from the James Hornell collection at the MAA, I was delighted to be given the opportunity to develop my experience in a different region by undertaking a Pacific Presences’ internship for the MAA at the National Museum of Ethnology in Japan (“Minpaku” as it is affectionately known). The Minpaku contains over 6,000 images taken during the expeditions of Charles Templeton Crocker, an American millionaire who financed the building of a luxury yacht, the Zaca, and began a series of scientific and anthropological research expeditions to the Pacific in the 1930s.

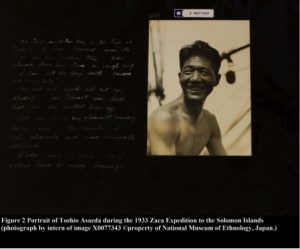

At the start of the work on January 26th, I was joined by researcher, Dr. Norio Niwa, and the Audio-Visual team at the Minpaku (Figure 1 above). They gave me an introduction to the material I was to review: a unique record of the Templeton Crocker expeditions made by Japanese photographer and artist, Toshio Asaeda (Figure 2). Toshio Asaeda, born in Tokyo in 1893, arrived in 1923 to the USA as an international exchange student. From 1925 to 1927, he began employment at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, accompanying the author, Zane Gray in travels to the South Pacific in 1931. From 1932 he became a regular member of Charles Templeton Crocker’s research expeditions, working as an artist, photographer and map-maker. His collection of photographs, diaries, and artwork were donated by the Asaeda family to the Minpaku museum in 1986.

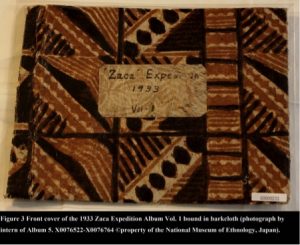

The focus of this internship was specifically to undertake a scoping exercise of the records at the Minpaku from the 1933 Scientific Expedition to the Solomon Islands, and the 1934-5 Scientific Expedition to South Pacific for the American Museum of Natural History. Before starting the work, I had previous contact with the collection through an internal database of digital photographs and inscriptions from the collection. However, this experience was entirely transformed when I was given access to the original images, which form part of a series of 16 photograph albums, hand-made and bound in materials (barkcloth for albums from the Pacific) sourced from the expedition by Asaeda (Figure 3 below).

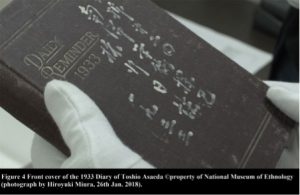

Having cast my eye over the diaries with Dr. Niwa at the beginning of the internship, it became clear that my Japanese skills would be nowhere near sufficient to translate the text, which was written mainly in a cryptic mix of Japanese characters with a few scattered English words resulting in a highly nuanced, diary short-hand, difficult to understand even for a native speaker of Japanese (Figure 4 above).

Whilst many of the photographs from this collection can also be found in the Templeton-Crocker collections at the MAA, it felt important to capture these images again in the format of these albums to understand the expeditions as told through Asaeda’s experience. It was decided, therefore, that the bulk of my time would be devoted to photographing and collecting data from Volumes 1, 2 & 3 from the Zaca 1933 Expedition, and Vol 1. & 2 from the 1934-5 Templeton Crocker Expedition. The images had been meticulously documented on the Minpaku’s database which considerably sped up the work. However, as each page of the albums is stored for conservation purposes in plastic film, I spent a week in the office experimenting with tripods, lighting, and multiple camera settings to try and avoid the glaring reflections from the shiny covers to capture the albums in as much detail as possible.

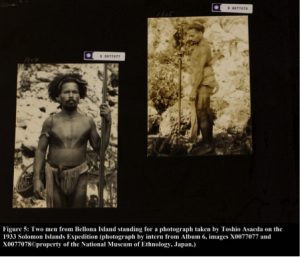

It was no easy task, but motivated by the beautiful work of Asaeda, and recognising the importance of capturing the record of these expeditions as experienced through this unpublished account, I was determined to get as many photographs as possible. In a short time, I was completely absorbed in the albums and took great pleasure in learning more about the geography of the Pacific and the diversity of its island cultures (such as, Bellona and Santa Catalina Island in the Solomon’s, Figure 5 & 6 below).

This collection is enriched by Asaeda’s artwork, a series of watercolours of marine sea creatures produced after the expeditions, and artistic impressions of his life from 1942-1945 when he was imprisoned in the USA at a Japanese internment camp. Experiencing this part of the collection, it was poignant to reflect on the life of an individual, who had collaborated with American peers, free to roam the seas, daring to undertake incredible voyages, risking his life on many occasions for the purposes of scientific research and museological collection, to then be confined and cut off from the world for many years.

It was a privilege to experience a collection which represents an important historical and artistic record by a Japanese photographer who has made a significant contribution to anthropology and photography, fields which in his day were dominated by Europeans and Americans. Not only is Asaeda’s work an exceptional legacy relevant to the history and cultures of the Pacific islands, but these incredible encounters are brought to life by a man who witnessed this world through a unique cross-cultural lens, using his creative and artistic abilities to record the history of the people and customs of the Pacific’s distinctive and diverse cultures.

Hannah Eastham, March 2018.

Posted on November 17, 2017 in Uncategorized

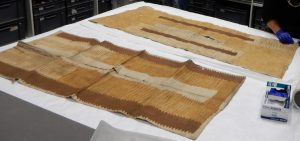

On 16 October 2017, photographer Mark Adams and project PI Nicholas Thomas visited the Etnografiska Museet, Stockholm -an impressive and innovative museum, though one housed in a rather ordinary red building from the 1980s, which gives little initial sense that some collections date back to the renowned eighteenth-century scientific societies and travellers associated with Linnaeus. Their particular interest was in an unusually large barkcloth, thought to have been collected during Cook’s first voyage. In this blog post Nicholas writes about their discoveries.

The barkcloth forms part of an important early collection given by Joseph Banks to Stockholm merchants and naturalists, the Alstromers, published by Stig Ryden in The Banks Collection (1965). Although the collection includes clubs from Tonga which cannot have been collected during the first voyage, Ryden assumed that Banks was the field collector of most of the material and published the textile (1848.1.13) as Tahitian, associating it with a formal welcome soon after the arrival of the Endeavour in April 1769, when Banks wrote of being presented with a large piece of cloth. Until we looked at the bark cloth on Monday – with the help of the really wonderful Stockholm team, who put in a lot of time to make this possible – the cloth had not been examined for many years.

As the piece was unrolled – our excitement mounted – it became apparent that it featured a typically Tongan rubbed design and reddish-brown colouring, and could not be what it had been identified as. In fact the cloth is very similar to an example in the Pitt Rivers, 1886.1.1238, which is part of the collection presented by Johann Reinhold Forster to the University of Oxford, following his return from Cook’s second voyage. That work also includes the same freely marked diagonals and lines along the otherwise plain fringe.

However, it is not cut from the same example – on the Oxford piece a diagonal and vertical rubbed pattern alternates whereas this features only a diagonal, rubbed from the same board along the full length and in reflection on both sides of the Stockholm piece. (The latter, approximately 14.77 x 2.6 metres, is also about 40 cm wider than the one in Oxford). There are related ngatu in Göttingen, probably also collected by Forster (Oz 576, 577). However the affinities are close enough to imply that the Stockholm example was from the same community of makers; it was no doubt acquired by one of the Forsters or some other participant in Cook’s second voyage, given to Banks and by him to the Alstromers.

This seems to be the largest piece of bark cloth with a Cook voyage provenance which remains extant. This clarification of its provenance may be valuable for those researching early Tongan ngatu.

It is however unfortunate, indeed tragic, particularly in the context of a revival of Tahitian interest in barkcloth, that no large Cook voyage example – the gift in its integrity – appears to have been preserved. While there are many textual references to presentation of textiles of this size, the only very large surviving cloth appears to be the one in Cambridge, likely to have been presented 50 years later to the LMS missionary George Bennet; though an eight-metre section thought to have been acquired by James Wilson during the voyage of the Duff which established the London Missionary Society is in Newcastle (thanks to Julia Lum for this information). And special thanks to Anna Fahlen, Aoife O’Brien and Stockholm colleagues for their generosity.

Nicholas Thomas 2017

Posted on October 2, 2017 in Uncategorized

In this blog entry Pacific Presences intern Ilka Kottmann describes here a long term collaboration between the project and Maori researchers on Maori hoe:

On the morning of June 8th 2015 a group of Pacific Presences researchers and associates came together to share an unforgettable moment in the South of Germany. The Linden Museum, Stuttgart kindly provided a large group of us from New Zealand, England and Germany access to a couple of very special Maori hoe or ‘paddles’ held in their archives.

From left to right: Julie Adams, Steve Gibbs, Areta Wilkinson (next to Steve), Mark Adams, Anne Salmond, Amiria Salmond (next to myself), Ilka Kottmann and Ulrich Menter.

(photo courtesy: Billie Lythberg)

The crosscultural hīkoi of the excellently preserved hoe on the right started some 248 years ago three miles offshore, somewhere between Whareongaonga and Tikiwhata south of Poverty Bay on the East Coast of New Zealand. In this particular case, after a rough start in Poverty Bay, the Crew of the Endeavour having had violent encounters on landfall with local Maori iwi, with subsequent killings. These two paddles presumably originated from the well documented trading incident on the Endeavour on October 12th 1769 just South of Poverty Bay, off the East Coast of New Zealand, when seven waka taua, Maori war canoes with around 50 crew approached the Endeavour. Local historian Mackay[1] describes the trading incident on the first Cook voyage after leaving Poverty Bay in detail:

‘The Endeavour made slow progress to the southwards. At noon, she was held up by a calm three miles off-shore at a point between Whareongaonga and Tikiwhata. Several canoes made their appearance, but stood off about a quarter of a mile. A canoe was then seen approaching from the direction of Poverty Bay. Banks says that it had four people on board, including one whom he well remembered seeing on the rock in the [Turanganui] river. Its occupants did not stop to look at anything, but went at once alongside the ship and, with very little persuasion, stepped on board. Their example was followed by the occupants of the other canoes, seven in all, and containing fifty men.

Gifts were freely made to the visitors, and they quickly parted with almost everything that they had with them, even their clothes, in return for Tahitian cloth. The occupants of one canoe, after selling their paddles, offered to sell their craft.’

This historic incident is the beginning of a crosscultural journey of Māori hoe hopefully to be continued.

From left to right: Mark Adams, Billie Lythberg, Amiria Salmond, Ilka Kottmann and Ulrich Menter examining the Linden museum hoe S 40235 in more detail.

(photo courtesy: Steve Gibbs)

This hīkoi or ‘long journey’, as reflected in this blog, is not a protest march but a walk into a shared Māori-European history. In this particular case it documents peaceful exchange and mutual enrichment, which started on the East Coast of New Zealand back in 1769. It’s a hīkoi of crosscultural exchange which in my perception is continued again today by Pacific Presences project work, by sharing images and stories and perhaps loaning the real paddles for the Cook celebrations in New Zealand in 2019. As Amiria Salmond has recently asserted:

‘Today the paddles are attracting great interest in the Tairawhiti region as taonga (treasured ancestral artefacts) of the local Maori people. Their importance as early examples of kowhaiwhai painting has been recognised by those engaged in the revitalisation of Maori arts, and research is in progress to establish their genealogical connections to present-day Maori communities’. [2]

The various hoe now present in England, Germany and New Zealand are symbols of the very first peaceful encounter of Maori and Endeavour crew. These hoe have inspired the artwork of Steve Gibbs of Ngai Tamanuhiri, a kin-group whose ancestors may have been among those who exchanged the paddles with Cook’s crew[3] and hopefully to be continued at the Cook celebrations in 2019 when these amazing hoe may travel as a loan across the oceans once again to their origin at the East Coast, to be honoured and greeted by the descendants of their makers.

Amiria Salmond and Steve Gibbs were particularly excited about the evident similarities between the red ochre kowhaiwhai paintings on the blade of S 40325 and one particular sketched blade by Parkinson, drawn in water colour on the spot on board the Endeavour in October 1769.

Oceania curator Ulrich Menter from Linden Museum helping us compare the excellently preserved actual blade of S 40325 held in their archives with images on Amiria Salmond’s laptop: Paddle blades from top to bottom on the screen are 1) Parkinson sketch from the Endeavour in 1769 and 2) C 589 held in the Hancock Museum, Newcastle.

(photo courtesy: Billie Lythberg)

Steve Gibbs’ subsequent visit to Newcastle as well as another close look at the images of the Newcastle paddle confirmed, that C 589 held in the Hancock Museum, Newcastle was the one sketched by Parkinson. Yet, the similarities between the Stuttgart and Newcastle paddles are striking and they are clearly from the same incident.[4]

Steve Gibbs in Newcastle holding the hoe C 589 depicted in the Parkinson sketch (photo courtesy: Steve Gibbs)

Artwork by Steve Gibbs – titled ‘Takoha’, painted on Tapa. Takoha refers to the custom of gifting and that things will be returned. In the second image he placed the real hoe from the Hancock Museum onto his tapa painting.

(Photo courtesy of Steve Gibbs)

Artwork by Steve Gibbs – titled ‘Takoha’, painted on Tapa. Takoha refers to the custom of gifting and that things will be returned. In the second image he placed the real hoe from the Hancock Museum onto his tapa painting.

(Photo courtesy of Steve Gibbs)

To me personally, these hoe from waka taua of the East Coast of NZ are a symbol of the continuum of fruitful cultural connections into our present time. One of many unique ‘Pacific Presences’ in Europe coming back to life again – in this case by the incredible artwork of Steve Gibbs, his upcoming PhD thesis as well as collaborative writings of Amiria Salmond, Billie Lythberg and Steve Gibbs for the forthcoming Pacific Presences book publication.

Ilka Kottmann 2017

[1] Joseph Angus Mackay, 1949, Gisborne: Historic Poverty Bay and the East Coast, N.I., N.Z., p.41

Part of: The New Zealand Provincial Histories Collection

[2] Salmond, Amiria, 2016. ‘“Their paddles were curiously stained”: two Māori paddles from the East Coast’, in Adams, Julie, Thomas, Nicholas, Nuku, Maia and Salmond, Amiria (eds.) Artefacts of Encounter: Pacific voyages and museum histories. Dunedin and Cambridge: Otago University Press and Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, pp. 118-121.

[3] Ibid.

[4] pers.comm. Amiria Salmond

Posted on September 4, 2017 in Uncategorized

Eve Haddow, a PhD candidate at the Australian National University has been working as an intern for Pacific Presences, recently her research took her to Vanuatu. In this blog post she describes her research and its exciting findings:

Readers of the Pacific Presences blog may be familiar with the collection of Admiral Edward Henry Meggs Davis, which Research Associate Dr Ali Clark has been investigating in detail. The collection of 1446 ethnographic artefacts from the Western Pacific was acquired while Davis was in command of the H.M.S. Royalist, 1890-93. As a Pacific Presences intern I have been exploring the material Davis acquired from Vanuatu (462 items). I recently returned from fieldwork in Vanuatu, where I hoped to find out if there were any contemporary ni-Vanuatu perspectives on the collection, and on the historical activities of H.M.S. Royalist.

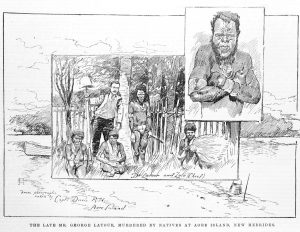

The Royalist travelled through Vanuatu for just over 6 months in 1890. At that time, Europeans collectively called the islands the New Hebrides/Nouvelles Hébrides, as named by Captain Cook. Davis and his crew were tasked with maintaining a British naval presence in the area, often responding to incidents with force – it is no coincidence that ships such as the Royalist were commonly referred to as a ‘man-of-war’. Davis intervened in a number of disagreements between ni-Vanuatu and traders living in the region, as well as disputes involving recruiters engaging people in indentured labour for plantations in Queensland, New Caledonia, Fiji and elsewhere in Vanuatu.

When I first looked at the list of items that Davis collected in Vanuatu, two things struck me. First was the sheer number of bows and arrows he collected (25 bows and a whopping 300 arrows!). Reading naval reports from the time, it seems likely these items are connected with Davis’ confiscation of weapons. Second, was the association of one artefact with a named individual (Fig. 1). In Davis’ catalogue of his collection, he lists a ‘pig hammer of TAPPEA’, with a note: ‘chief of Aure ID New Hebrides’. This is noteworthy as only three original owners are named within the entire catalogue. I wondered who Tappea was, and what had happened to make Davis record his name?

‘Aure’ and ‘Aura’ are 19th-century names for the 58km² island of Aore, situated on the south coast of Vanuatu’s biggest island, Espiritu Santo. Aore is a short boat trip across the Segond Channel from Luganville, the largest town on Santo and second largest in Vanuatu with a population of around 12,000. Today, as in 1890, a much of Aore is home to coconut plantations. There is also a coffee plantation, Aore Academy (a Seventh Day Adventist secondary school), and several expensive holiday resorts. Figures compiled in 2010 indicate 65.3% of Aore was leased (Scott et al. 2012: 3). This is an extraordinarily large amount of alienated land when compared with other islands in Vanuatu. When I arrived in Luganville, I was repeatedly told there is ‘no man Aore’. Many claim the last of the local population was forced to leave the island sometime in the early 20th century, as people were being poisoned by a European plantation owner.

On Aore, I met Chief Takau Muele, one of the current Chiefs of Aore, Malo, Tutuba and Mavea islands (Fig.2). He and his parents were born on nearby Malo, but have ancestral connections to Aore, making him a traditional landowner. Chief Takau has a great knowledge of the culture and history of the area. Sitting in his house on Aore, I showed him an image of Tappea’s club. Chief smiled, and asked his daughter Joyce to reach under his seat for his own club, which was a very similar style to Tappea’s (Fig. 3). He told me that in his Malo language it is a wawusa, made of wood of the aru tree, and associated with pig killing ceremonies.

Chief Takau’s late father told him the story of a man named Tartappea of Aore, who had been taken by white men on a ship to Noumea. Newspaper reports of the time say Tappea was sentenced to 15 years hard labour by the French government for murdering the crew of the ship Idaho, and Chief Takau told me Tartappea never returned to Aore. Through oral and archival sources, I’ve been able to unravel the tangled web of events on Aore in 1890. Tappea was picked up by Davis following the complaints of a plantation owner named George De Lautour. This Englishman, who settled on Aore in 1885, was embroiled in local politics and often involved himself in disputes with islanders, planters, recruiters, and missionaries alike. A diary kept by Lautour for the year 1887, held at the National Museum of Fiji, gives a glimpse of Lautour’s bad-tempered nature. In April 1890, Lautour informed Davis that two men, Tappea and Thor, had kidnapped his ‘housekeeper’. Davis investigated the matter, and it was he who sent Tappea to Noumea for trial. In September 1890, a report reached Davis that Lautour and his 19-year-old son were dead, apparently murdered by Thor and some men from Malo. Thor claimed his actions were retribution for Lautour’s murder of two people on Aore, and for destroying Thor’s possessions and banishing him from the island.

The Royalist returned to conduct an investigation. After a short time gathering statements, with the Presbyterian missionary on Malo acting as interpreter, Davis found Thor and two men from Malo guilty, and sentenced them to death. In a show of colonial power, Davis had the men executed by firing squad. Chief Takau Muele’s father told him a story of four males from Malo who were involved in the incident, two he described as boys. The events were reported in the Australian press, with an obvious bias towards Lautour.

The details are shocking, with reports of 80 British naval officers landing on Aore for the execution, and other papers erroneously reporting that Lautour’s son was eaten, despite all official records contradicting this. Davis received criticism from the Western Pacific High Commissioner for his violent actions, and his misplaced involvement in what the Commissioner deemed a ‘domestic dispute’.

What has emerged from my research of Tappea’s club is a story of murder, injustice, colonial violence, politics and land, the traces of which are present in Vanuatu today. It is one of few artefacts I’ve been able to identify in museums as from Aore. After being told in Vanuatu there is ‘no man Aore’, the club now seems a rare material connection to Aore’s past. Tappea’s club might seem as symbolic of loss and colonial violence, if we consider the events of 1890 and the decades that followed, culminating in this claim of ‘no man Aore’ and the land alienation of over 60% of the island. But it is simultaneously a tangible link to the rich cultural history of Aore and surrounding islands, and provides a platform for exploring multiple aspects of this history with it’s echoes in contemporary Vanuatu.

I am currently writing this research into a chapter for Dr Clark’s forthcoming publication on the Admiral Davis’ collection. This will, I hope, be a chance to delve deeper into some of the emerging themes and to share more of this complex story.

Eve Haddow 2017

Posted on July 12, 2017 in Uncategorized

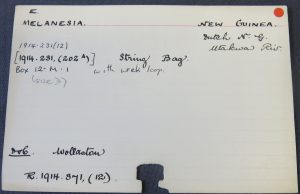

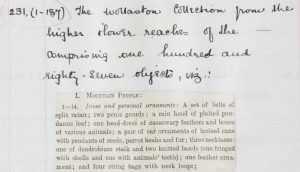

In a previous blog, I described the different numbers associated with the collection of Alexander (Sandy) Frederick Richmond Wollaston, and how these many sets of numbers might have come about. The most problematic aspect is that most objects are not inscribed with their Accession Register number, which was standard practice, but instead with a number that comprises of the year of accession, the collection number and a suffix based on the numbers used by Alfred Cort Haddon and John Willoughby Layard in their Report on the Wollaston collection.[1] This has continuously created confusion for all researchers willing to engage with the Wollaston collection. Quite a few attempts were made over the years to understand this situation. If one started with the catalogue cards, one was warned right away by an inscription on one of the cover cards to the Wollaston collection: ‘Part, at least, of Wollaston collection seems to have been accessioned twice, as these nos. overlap. Beware + good luck!’

The first documented effort to make sense of the different numbers on the objects[2] and in the Accession Register was undertaken in the late 1970s by Mrs Joan Cunning, a retired librarian from Melbourne, Victoria, and Honorary Keeper of Records between 1975 and 1980. In these five years, she was ‘checking and sorting the catalogue cards referring to specimens acquired between 1883 and 1919’ and ‘matched the accession lists with the entries in the annual reports’.[3] Even though the majority of the catalogue cards give the prefix+H&L2 number at the top and the Annual Report number[4] at the bottom, as can be seen in the example below, Mrs Cunning could not relate the prefix+H&L numbers (which were also inscribed on the objects) to anything else. Moreover, there were gaps in the series, which made it even harder for her to understand. A note in the Accession Register 9 (p. 57) in Mrs Cunning’s hand explains that ‘[T]his collection has been labelled with a curious collection of numbers not corresponding to the register or the Annual Report.’ It is thus likely that Mrs Cunning did not have the Haddon and Layard report to hand,[5] when working on the Wollaston collection.

Nevertheless, she added the Accession Register number just above the prefix+H&L numbers on top of most of the catalogue cards (cf. image above). Additionally, she noted in pencil the specific Accession Register number on top of every object in the Accession Register, as can be seen in the image below.

Extract from the Accession Register number 9, page 57, showing the specific accession number written in pencil on top of the objects.

After more than 20 years, the next important step in unravelling the riddles of the Wollaston collection was undertaken by Karen Jacobs, now Lecturer in the Arts of the Pacific at the Sainsbury Research Unit, University of East Anglia, who researched the Wollaston collection for her PhD on Kamoro Art and Collecting in 2004. In the meantime, the collection had been taken off display, and had been stored in numerous different boxes and on racks in the back rooms of the museum. Having conducted research at the Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde in Leiden, Netherlands[1], Karen Jacobs found a copy of Haddon and Layard’s report at the Library there and brought a working copy of it with her to Cambridge. Therewith she was able to compare the objects with the descriptions and sketches in the report, reconnect the Accession Register number with the prefix+H&L number on the objects and verify the connections made earlier by Mrs Cunning. In addition, she wrote new labels which she attached to the objects found, and compiled an important report on the collection, including a vast amount of information from Haddon and Layard’s report and other sources.[2]

However, there remained some oddities which couldn’t be explained – why was it not possible for Joan Cunning, Karen Jacobs and myself to correlate some of the objects we found during our research with any of the Accession Register numbers, even though these objects were obviously part of Wollaston’s collection, as the typical labels proved.

So far, six such objects could be located. They are mentioned in Haddon and Layard’s report and show the typical square adhesive label with the H&L number. After checking the list of objects that were returned to Wollaston it seems indeed that these objects were part of the gift to the museum. But why are they then not mentioned in the Annual Report or in the Accession register?

Clues in the paper archive

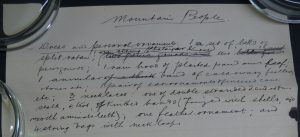

In museum (and probably many other) archives, sometimes notes survive, which in regular circumstances probably would have been scrapped. Two such examples, one handwritten and one typewritten list, were found in an envelope labelled ‘Combined lists (roughs) used for compiling the list of Wollaston Collection (Utakwa River) D.N.Guinea, for 1914 list in Annual Report’. Looking through these lists, I found some of these six objects.

The first example can be seen in the image below. It is ‘one strung phalanger humeri’[3] on the ‘Mountain People’ (Amungme) list, which was written in between the lines and therefore could easily be overlooked. This head dress of upper arm bones of a marsupial is depicted and described in Haddon and Layard’s report as the number 216. The object found in the stores does indeed match the sketch in the report and bears the prefix+H&L number 1914.231.216. However, it was never recorded in the Annual Report, and as the Annual Report was used to create the entries in the Accession Register, it was not given an Accession Register number.

Similarly, a ‘rain hood pandanus leaf’ (prefix+H&L number 1914.231.141) was written in the top right corner of the ‘Coast People’ (Kamoro) handwritten list, but was missed during the transfer into the Annual Report.

Two other objects, namely a string that is holding a penis gourd (H&L number 207) and a tassel which would have been attached to the gourd (H&L number 208), are not mentioned in the Annual Report. They seem to have been sacrificed to the necessity ‘to abbreviate as far as possible the description of specimens in the Accession List’, as stated in the Annual Report for the year 1914, page 4. While they have been described and depicted as one set in Haddon and Layard’s report (see below), in the handwritten list (above) it reads ‘two penis gourds and two belts for penis gourds’. The words ‘two penis gourds and’ and ‘belts for’ were crossed out with pencil, leaving the words ‘… two … penis gourds’. Even if the string and the tassel are not mentioned in the Annual Report, it seems likely, that the abbreviation ‘penis gourd’ would refer to the whole set, and not just the gourd, especially, as all three objects remained at the MAA.

Extract from Haddon and Layard’s ‘Report on the Ethnographic Collection from the Utakwa river made by A.F.R. Wollaston’ (1916: 8).

Finally, there are two canoe prow ornaments (1914.231.242 and 1914.231.243) without an Accession Register number. The lists describe the prow ornaments in plural, whereas the Annual Report only mentions one prow ornament. Mrs Cunning, who came across one of them[1] in the 1970s and was unable to find a corresponding Accession Register number, decided to add this object (H&L number 242) to the Wollaston collection and to give it the next following Accession Register number: 1914.231.188. Admittedly quite a creative solution as the collection is everywhere noted as comprising of 187 numbers, but also a clever one, as it allowed the object to be identified as part of the Wollaston collection but without colliding with numbers already assigned to objects, as in the case of the rain hood with the prefix+H&L number 1914.231.141 to which an arrow exists with the Accession Register number 1914.231.141.

A possible hint to the reasons for these omissions in the Annual Report might be between the lines of the Annual Report for the year 1914 (page 4), where one can read: ‘WORK DONE. Lists of Accessions numbering over three thousand objects received during the four years 1910 – 1913, have been compiled by the Curator and issued with the belated annual reports for 1912 and 1913. […] Lack of show-cases has retarded work. It becomes more and more difficult to supervise the specimens and secure them from damage by moth etc., so long as the bulk of the collections remain packed up in boxes.’ If one thinks about compiling lists for the Annual Report under these circumstances, it seems understandable that some of the objects, although present at the museum, might have slipped the close attention of the Museum personnel compiling the lists.

Having found these explanations, I went back to the excel-file I compiled as part of my research, which I have organised according to the Haddon and Layard numbers. I checked how many other objects from the collections were not returned to Wollaston but are not mentioned in the Annual Report either and therefore could / should still be at the museum. I found another three.

The hunt is on!

Katharina Wilhelmina Haslwanter

[1] An image of this object can be found in the previous blog on the history of the Wollaston collection.

[1] Since 2005 the museum is called Museum Volkenkunde and since 2013 it is part of the museum group Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen (National museum for World cultures).

[2] Jacobs, Karen (2004). Report: analysis of the collection assembled by A.F.R. Wollaston in Dutch New Guinea (1910- 13). Unpublished Crowther-Beynon Fond report on the Amungme objects in the Wollaston collection.

Jacobs, Karen (2004). ‘Coast People’ or the Kamoro collection assembled by A.F.R. Wollaston in the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge University. Unpublished Crowther-Beynon Fond report on the Kamoro objects in the Wollaston collection.

[3] An image of this object can be found in the previous blog on the history of the Wollaston collection.

[1] Haddon, Alfred C. and Layard, John W. (1916). Report on the Ethnographic Collection from the Utakwa river made by A.F.R. Wollaston. In: British Ornithologists’ Union. Report on the Collections made by the British Ornithologists’ Union Expedition and the Wollaston Expedition in Dutch New Guinea 1910- 13, 2 vols. Francis Edwards, London, 1916, Vol. II, part 19.

[2] The number inscribed on most objects comprises of the accession year, the collection number and the Haddon and Layard suffixes. I will refer to this number as prefix+H&L number.

[3] Cf. the Annual Reports of these years, for the quotes esp. 1974-75 page 2 and 1977-78 page 5 as well as the pencil entry in the Accession Register 9, page 57.

[4] Accession Register number and Annual Report number do only differ from each other in the collection number in the middle, but prefix and suffix are the same. The same object would be 1914.371.33 in the Annual Report, but 1914.231.33 in the Accession Register.

[5] There is a copy of Haddon and Layard’s Report in the archive of the MAA (Doc.58), but it is unclear since when. However, even if it was already there when Mrs. Cunning was working on the collection, she might not have known about it or did not find it. Even though the archive was first sorted in 1967 by the then Assistant Curator Marilyn Strathern, Haddon and Layard’s Report got registered as Doc.58 only in 2006 by Imogen Gunn.

Posted on June 26, 2017 in Uncategorized

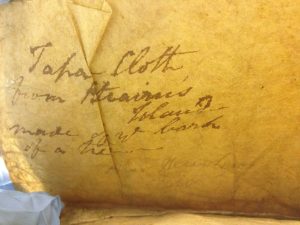

Over three weeks in April 2017, Pauline Reynolds, a visiting researcher with Pacific Presences, various museums in order to study tapa made by my foremothers. This began with attending the second day of the Museum Ethnographers Group conference in Glasgow, a fitting way to begin my collaboration with Pacific Presences and contextualise my visit.

The first museum visit was to King’s Museum with Lucie Carreau where a beautiful example of a Pitcairn tiputa (something like a poncho) is held. I’m particularly attached to one of these examples, because we know the name of the maker, it shows signs of wear and tear, and it has become familiar to me, like an old friend. The curator Louise Wilkie had discovered another two cloths – one a tiputa, and another a length of undecorated white tapa, which made the day exceptionally successful. The tiputa at the top of the photo here was made by Dinah Adams, the daughter of Vahineatua and mutineer John Adams

Photo by Lucie of refs ABDUA 4007 and 4008

In Glasgow we visited the Centre for Textile Conservation where the research project ‘Situating Pacific Barkcloth Production in Time and Place’ is operating, and viewed examples of Pitcairn tapa from the Kew collections and the conservation techniques used in their care, and spoke extensively with the conservation team including Andy Mills, Frances Lenndard, Misa Tamura and Beth. This was followed by a visit to the Glasgow Museum Resource Centre guided by Ed Johnson and Pat Allan, where we were able to observe a range of different coloured cloths – one dyed a stunning rich yellow dye, another a dirt brown, another cloth was so fine it resembles a loose gauze.

Photo by Lucie of ref 79-42 hj

I had met Michaela Appel at the Made in Oceania conference in Cologne in 2013, and she was sure that the Five Continents Museum in Munich had a tiputa similar to the King’s Museum example. Sure enough, when I visited with Erna Lilje, I recognised the unmistakable patterning that is unique to Pitcairn tiputa – it is a fine example. While we were there, Hilke Thode-Arora and Michaela showed us a large range of beautiful Polynesian tapa, part of an extensive and fabulous collection.

MUNICH photo by Pauline ref. Inv. Nr. 131

One of the great strengths of participating in Pacific Presences from my point of view is being able to engage in worthwhile and inspiring exchanges with the Pacific Presences team, in particular Lucie and Erna, while observing Pitcairn and Tahitian tapa. At the British Museum’s Blythe House stores, we saw a number of tapa that I had seen before, but observing them with Lucie Carreau, Julie Adams, Jill Hassell, and my daughter, allowed for vigorous discussion around a range of issues: colour, dye, size, technique, use, the effects of conservation … as well as exacting observations – the width of beater grooves used and other techniques. We required two full days at the British Museum stores, and could easily have stayed another, examining the wide range of cloths.

British Museum group photo by Pauline

Throughout my research I have found it most helpful to ask myself the following questions when collecting data about tapa and related objects:

What is it, what are its qualities?

Who made it? Who gave it?

When was it gifted or collected?

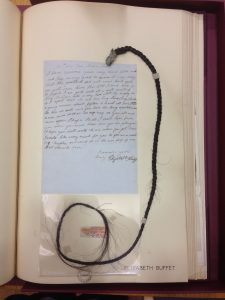

It is sometimes possible to build a picture of a Pitcairn woman and her relationships by the gifts she gave. Hannah, Dinah’s sister (who made the Aberdeen tiputa in the photo above), wrote to Rear Admiral Lowther who had visited Pitcairn in the 1850s, expressing herself eloquently in both Tahitian (her mother’s language) and English, an important revelation showing that Tahitian was still fluently spoken on the island at that time. This letter, along with another written by Hannah’s daughter Elizabeth Buffett, is located at the Centre for Anthropology in the British Museum. Elizabeth also gifted a finely made cloth to a visitor to Pitcairn in 1850, of which a small section is today at Hastings Museum.

British Museum Library of Anthropology photo of Elizabeth Buffett’s letter to Lowther and a lock of her hair

HASTINGS MUSEUM tapa, photo © Hastings Museum & Art Gallery

There were a number of surprises in the collections we visited. Newly discovered cloths in various locations could possibly mean that my database of Pitcairn tapa will be forever expanding. Incorporating these items into my expanding documentation has allowed my profiling of the Pitcairn women to expand and fill in gaps I thought would always remain a mystery.

Finally, a visit to Pitt Rivers with Nicholas Crowe and Faye Belsey was impressive, discovering another “new” tapa, observing conservation techniques, and a fine collection of archaeological objects from Pitcairn and around the world, while time in Cambridge allowed me to visit a number of important items at the MAA, give an informal talk about my visit, and learn from the wonderful team of the Pacific Presences Project.

These tapa act as vessels, transporting me back through time, where (if I’m lucky) I might catch the scent of the air at the time of its production, imagine the maker’s mindset, marvel at her skills, and puzzle over her choices. This is a personal journey of discovery and genealogy, but also one that will eventually benefit all descendants of these amazing women. I was struck by the care and attention, and attachment that curatorial teams hold for each of these tapa: which is heart-warming considering the Pitcairn tapa are genealogical markers for my people. I benefited from the robust conversations around tapa during my research trip with all of these curators, and the Pacific Presences team.

Pauline Reynolds, 2017.

Posted on June 4, 2017 in Uncategorized

Katharina Wilhelmina Haslwanter is a PhD student from Zurich University and an affiliated researcher of the Pacific Presences project. In the following two blogs, she presents some of her recent research findings on the Wollaston collection, and therewith gives insight into the early history of MAA.

In summer 2015 and January 2016, I was researching the western New Guinea[1] collection from Alexander Frederick Richmond Wollaston at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA) as part of a Doc.Mobility research fellowship from the Swiss National Science Foundation. During my current internship with the Pacific Presences project I decided to take up my research on this collection again, trying to solve the puzzles surrounding the numbering of this collection.

Dr Elisabeth Blake, who kindly helped me during my research in 2015 / 2016, has already given a fascinating insight into the 1912-1913 Wollaston expedition in a previous blog post. I would like to complement her account with additional information on Wollaston and his expeditions as an introduction.

Alexander (Sandy) Frederick Richmond Wollaston (1875-1930)

Sandy Wollaston, a British ornithologist, medical doctor, botanist and explorer, participated in two expeditions to Dutch New Guinea. Both expeditions moved from the south coast into the island’s interior with two aims: to collect scientific specimens and to reach the snow-covered mountains of the Nassau Range (now Sudirman Range). The first expedition was undertaken by the British Ornithologists’ Union in 1910 and 1911. While bringing back diverse collections, they did not get further than 40 km inland let alone reach the mountains, as the expedition was ‘poorly planned and deliberately misdirected by the Dutch authorities’[2] towards the Mimika river.

Disappointed by this defeat, Wollaston decided to try it a second time following another river route. With financial support from the British Ornithologists’ Union and private benefactors, Wollaston himself led a second expedition to western New Guinea in 1912-1913. This time they followed the Utakwa (today Otakwa) and Setakwa Rivers from the south coast up to the Tsingarong and Bandarong Rivers, and finally managed to reach the base of the glacier, which covered the higher region of the mountain range. However, they could not get further, because they didn’t have the right equipment nor the necessary experience to tackle the glacier.[3]

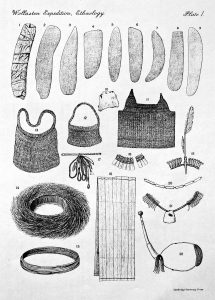

Nevertheless, the members of the two British expeditions collected important natural history specimens and ethnographic material and documented their encounters with the Papuans in photographs and in notes. The ethnographic collection is diverse, ranging from clothes and body decorations, tools and weapons to musical instruments and carvings, as the following two images demonstrate.

Headdress made of 99 humeri (upper arm bones) of a phalanger (a marsupial) from the Amungme (prefix+H&L 1914.231.216).

Wollaston donated the biggest part of his object collection to the then called Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (MAE, the predecessor of today’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, MAA), namely 231 entries[4] representing 408 objects.[5] A further part of his collection (184 entries) is at the British Museum. Of the 231 entries at MAA, two third come from the Kamoro people which live in the lowlands at the south coast of western New Guinea. 79 entries come from the mountain areas, namely from the Tsinga valley Amungme and a group of people who probably were Ekari- or Moni-speaking[6] to which Wollaston referred to as ‘Tapiro’.

Already during my research on the Wollaston collection in summer 2015, I was puzzled by the many different sets of numbers associated with the objects. One object could bear up to four different numbers –as can be seen in the image of the prow ornament above – which made the search for an object entry on the digital database quite challenging. Moreover, in most cases there were at least two digital records for a single object. At the time, my research focused on the objects themselves –their use, origin and composition – not on their museum history. I remained, however, interested in understanding what generated multiple numbers and digital duplications. As part of the Pacific Presences internship, I decided to investigate the way in which the Museum handled the Wollaston collection once it entered its walls. Here, I would like to share what I have found so far.

Various sets of numbers

After his return from the second expedition, Wollaston loaned his collection[7] to the MAE, where the honorary keeper Alfred Cort Haddon and his assistant John Willoughby Layard undertook comprehensive research on it, comparing it with other specimens from the same region of origin, in the UK as well as at the Rijksmuseum Leiden in the Netherlands. The purpose of their research was the compilation of the Report on the Ethnographic Collection from the Utakwa river made by A.F.R. Wollaston, which was published in 1916 as part of the larger British Ornithologists’ Union’s Report on the Collections made by the British Ornithologists’ Union Expedition and the Wollaston Expedition in Dutch New Guinea 1910-13. Their report gives a detailed description of the object’s composition as well as information on their use and value as it was known at the time, and included eight plates with astonishingly accurate sketches of the objects, as can be seen in the example below. For their report, Haddon and Layard numbered the objects present from 1 to 257. This is one set of numbers[8] associated with the collection (which I will refer to as H&L numbers), usually found printed on square labels adhered to the objects.

Photograph of Plate I in Haddon and Layard’s ‘Report on the Ethnographic Collection from the Utakwa river made by A.F.R. Wollaston’ (Doc.58, MAA Archive).

When Haddon and Layard finished their research for the report, 105 objects were returned to Wollaston in March 1914. The rest of the collection remained at the MAE as a gift from A.F.R. Wollaston. It was then accessioned into the Museum’s Register, assigned with the only recently introduced three-part numbering system, which is a combination of the accession year (1914), the number of the collection (231) and a suffix for every individual object or object group. As there were 187 objects or object groups respectively, the Accession Register numbers for the Wollaston collection are therefore 1914.231.1 to 1914.231.187. It is important to mention that in the case of the Wollaston collection, the collection was first numbered for the Annual Report, where it has the numbers 1914.371.1 to 1914.371.187 (note the different collection number between the dots. This is another set of numbers.). Only after this, the collection was accessioned into the Accession Register, as cut out copies of the Annual Report glued into the Accession Register indicate.

Most of the objects however do neither bare the Accession Register number (which would have been and still is the rule), nor the Annual Report number, but a combination of the accession year, the collection number and as a suffix the numbers used by Haddon and Layard in their report, leading to a range of numbers between 1914.231.1 to 1914.231.257 (which I will refer to as prefix+H&L numbers).[9] This of course made it difficult to link the object to its corresponding Register number.

Let me illustrate this with an example. While the Register number for the object below – a string bag with a protective shield and a sliver of bone from the Amungme – is 1914.231.34, the object itself is inscribed with the prefix+H&L number 1914.231.219.

So far, I have not found any document that would explain why on the objects the prefix+H&L numbers were used instead of the official MAE Register numbers, which would have been the rule.

One reason for this might be linked to the fact that a big part of the Wollaston collection was on display[10]. If the Museum staff would have put the new Register numbers with the objects, the connection with the H&L report numbers and therewith the vast knowledge on the objects documented in the report would have been lost for the visitors. To make clear to which collection the objects belong, it might have been decided to add the accession year and the collection number to the objects as well. This could have led to the combination found on the object. However, this is only one possible explanation, and proof for it is needed.

I would like to close this blog entry by pointing out, that while our research privileges the physical objects –their use and construction, their origins and histories, their meaning to the people who made and used them and their descendants, as well as to people who look at them and work with them in museums now, and the many other aspects object research can involve – it is also part of our museum duty to retrace the journeys that bring objects to museums and to consider how they are processed within these institutions. It provides an important insight into the practice of museum work and the methods implemented in museums historically. Even if it might sound rather tedious to some, it is an exciting and important part of museum work, which can be highly satisfying, when one encounters a missing piece of the puzzle and suddenly the picture becomes clearer.

Katharina Wilhelmina Haslwanter, 2017

References

[1] With western New Guinea I am referring to the western half of the Island New Guinea, which is currently a part of Indonesia and organised into two provinces, Papua and Papua Barat (West Papua).

[2] Ballard, Chris (2001). A.F.R. Wollaston and the ‘Utakwa River Mountain Papuan’ Skulls. In: The Journal of Pacific History, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Jun. 2001), pp. 117-126: p. 117.

[3] Klein, Willem Carel (1954). Nieuw Guinea. De ontwikkeling op economisch, sociaal en cultureel gebied, in Nederlands en Australisch Nieuw Guinea, Vol. III. ’s-Gravenhage: Staatsdrukkerij- en uitgeverijbedrijf: p. 73-74.

[4] With ‘entry’ I mean an entry in the Accession Register. However, one such entry can comprise of more than one object, for example the entry 1914.231.35 is a jaw’s harp and its case, and therefore two objects.

[5] The biggest part of the collection was given in 1914, two smaller additions reached the Museum in 1924 and 1925.

[6] Cf. Ballard, Chris (2001). The British Expeditions to Dutch New Guinea (1909-13). In: Ballard Chris, Anton Ploeg and Steven Vink (eds.). Race to the Snow. Photography and the exploration of Dutch New Guinea, 1907-1936. Amsterdam: Royal Tropical Institute, pp. 27-34: p. 30.

[7] It was mainly his collection from the second expedition, but included some specimens from the first expedition.

[8] It was not the first set, though, as Wollaston had himself numbered the collection, as a little notebook in the British Museum archive reveals. And it was not the last set, as the collection has another number in the Accession Register (1914.231.1 to 187) and the Annual Report (1914.371.1 to 187). Finally, some singular objects bear an additional ‘Z Number’, which had been used in different ways over time, e.g. as a temporary number to objects that could not be correlated to a number in the Accession Register. This means that there are up to six numbers associated with some objects in the Wollaston collection.

[9] This range of numbers is of course incomplete, as 105 of the objects bearing H&L numbers have been given back to Wollaston.

[10] The Annual Report for the year 1928 notes that the Honorary Keeper of the New Guinea collection, Dr Haddon, ‘overhauled all the ethnographical specimens from Netherlands New Guinea, and installed as many as possible in the Andrews Gallery. The collections from the Utakwa River given by Dr Wollaston can now be conveniently studied.” The collection remained on display – with a brief interruption during the Second World War – until the refurbishment of the Museum in the 1980s.

Posted on July 28, 2016 in Uncategorized

Pacific Presences Visiting Research Fellow Anna-Karina Hermkens writes about her work on barkcloth for the project in relation to the recent Festival of Pacific Arts, held in Guam (22 May-3 June), and an extraordinary exhibition of reinterpreted Tongan barkcloth at the National Gallery of Victoria, Australia (10 June-11 September 2016). My research project for the Pacific Presences Project aims to describe and compare barkcloth (tapa) collected in ‘Melanesia’ and ‘Polynesia’ in the collection of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, detail and analyse its particular colonial representations, and relate these to current performances and discussions in Oceania about making barkcloth cultural heritage.

As part of this project, I was fortunate to be able to attend the Festival of Pacific Arts, held in Guam (Mariana Islands). The Festival of Pacific Arts, also called FESTPAC, is a travelling festival hosted every four years by a different country in the Pacific. The Festival was envisaged by the Conference of the South Pacific Commission (now the Secretariat of the Pacific Community, SPC) in an attempt to combat the erosion of traditional customary practices. Since 1972, delegations from 27 Pacific Island Nations and Territories have come together to share and exchange their cultures at each Pacific Arts Festival. The Festival “is recognized as a major regional cultural event, and is the largest gathering in which Pacific peoples unite to enhance their respect and appreciation of one another”.[i]

In Guam, which was the 12th country to host the festival, around 2,500 performers, artists and cultural practitioners showed their skills in canoe-faring, performed dances, music and poems, showcased their films and artworks, and sold and demonstrated ‘traditional’ arts and crafts, including barkcloth.

The Tongan delegation performing at FESTPAC, wearing layers of ngatu (barkcloth).

The pavilion of the Tongan delegation at FESTPAC with fine mats and ngatu.

Barkcloth, often referred to as tapa, but known as ngatu in Tonga, masi in Fiji and kapa in Hawaii, amongst others, is known and used across Oceania. In many Pacific Islands, people have been making barkcloth from the paper mulberry tree, but it is also being made from the inner-bark of Ficus trees. The cloths, which vary from small strips of loincloth to more than twenty metres-long pieces of cloth, are intimately interwoven with past and present socialities across Oceania. They have been used to decorate, wrap, cover, protect and carry the human body, as exchange valuables and commodities, in land claims, and as indexes and embodiments of ancestral power. It therefore comes to no surprise that tapa was very much part of the Festival of the Pacific Arts. Not only was it worn by many delegates during their dance performances, it was also sold as both raw material and decorated cloth, as framed paintings and as sculptures. Among those buying tapa were not just tourists and festival visitors. Pacific delegates exchanged pieces with each other and bought each others work. For example, Rapanui delegates, who value tapa immensely as it is part of their ‘lost’ cultural heritage which they try to reclaim, but also because mulberry trees are scarce on Rapanui, bought large pieces of undecorated white tapa from Tongan delegates, as well as a large piece of decorated Fijian tapa.

For the Samoan, Fijian, Tongan and Rapanui tapa makers I spoke with during the Festival, tapa is about their culture. As Fijian Talei Manara stated, “everything we do, we must wear masi (tapa)!” But it is also seen as something that connects Pacific Island societies with each other and the wider world. “Masi will send you around the world”, said masi maker Selai Buasala, who teaches her daughters how to make and design (paint) masi, just as her mother taught her. It opens up different pathways, enabling Pacific islanders, and especially local women, to travel in order to promote and sell their tapa work. But essentially, it is “about our place in the world”, as Moana Eisele from Hawaii expressed, about what it means to be Hawaiian, Tongan, Samoan, or Fijian.

Moana Eisele making Hawaiian kapa (tapa).

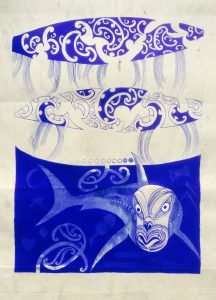

This capacity of barkcloth to reach out and at the same time create regional and local belongings and identity, has been taken up and pushed further by New Zealand-Aotearoa based printmaker and painter Robin White and Tongan artist Ruha Fifita in their collaborative project ‘Siu I Moana: Reaching Across the Ocean’, which is on display in the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne (Australia). In their vision, their collaborative series of re-interpreted Tongan barkcloth (ngatu) form a pathway, not only for Pacific Islanders, but also for humanity at large to come together and create connections. Importantly, White and Fifita’s project is part of the largest exhibition of contemporary Pacific art ever to be held in Australia this far. Stereotypically being classified as craft instead of art, Pacific arts such as painted barkcloth have predominantly been displayed in ethnographic museums. And while receiving recognition for their work in New Zealand and Europe, Pacific artists and their work have been structurally underrepresented in the Australian museum context. As such, White and Fifita’s ngatu has already proved to be a pathway for both Pacific arts and artists to enter the Australian gallery and art market and to finally receive recognition by one of Australia’s leading national galleries.

White’s and Fifita’s choice for barkcloth as their medium comes perhaps as no surprise as it is inherently part of Ruha’s Tongan ‘roots’ and referred to by White as “the DNA of the Pacific”. White and Ruha have imbued Tongan ngatu, which is traditionally used as ceremonial gift in weddings and funerals, as garment, and part of royal inaugurations and rituals, not just with artistic skill and significance, but also with new spiritual meaning.

Three of the eight ngatu (painted barkcloth) composed floating in a huge white cube, with the center piece (titled Seen along the avenue) stretching out towards the entrance, inviting the audience to enter the room and follow the halakafa – at once a pathway and, traditionally, a place for tying rope ‒ that runs through the middle of the ngatu and which leads to the sacred and the spiritual (Mt Carmel).

For White and Fifita, the collaborative creative process of working with the earthly materiality, timbre and temporality of barkcloth and traditional dyes, engendered a sense of wholeness. This wholeness has, as they hope, not only fulfilled themselves, but also imbued their ngatu with a significance that transcends the mere artistic. The layers of soft white ngatu, painstakingly painted with both old and new metaphorical and symbolic designs, are envisioned to wrap and bring people together, regardless of gender, age and ethnicity.[i] Siu I Moana is therefore indeed reaching across the Ocean, just like the Festival of Pacific Arts does. It connects people in the Pacific (Tonga and New Zealand) and in the Australian Pacific diaspora, but it also reaches out to all of humanity in the hope of engendering uplifting experiences of community, hope and renewal.[ii]

I hope that my project for the Pacific Presences Project generates similar forms of connectedness by connecting historical museum collections with present-day tapa makers, creating new understandings and valuations of tapa past and present.

[i] Ryan, Judith 2016. ‘Siu i Moana: Reaching across the Ocean.’ Essay. https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/siu-i-moana-reaching-across-the-ocean/

[ii] Interview with Robin White and Ruha Fifita, Melbourne 12 June 2016.

[i] https://festpac.visitguam.com/visiting-the-festival/about-the-festival

Anna-Karina Hermkens 2016

Posted on July 20, 2016 in Uncategorized

In February and March 2016 conservator Rachel Howie undertook an internship with the project, here she reflects on the work she did:

For two months I had the opportunity to research and conserve some amazing objects from the collection of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA), Cambridge. These included a porcupine fish helmet, and coconut fibre armour consisting of a cuirass, sleeves and overall-style trousers. The aim of the project was to conserve and mount the objects for display in a micro gallery exhibition at MAA in 2017, and for loan to the Royal Academy in 2018. In addition I had to research the materials, manufacture and use of the armour and helmet. This included looking at comparable examples in various UK institutions. In this blog post I will concentrate on the conservation.

Coconut fibre armour Z 7034

The cuirass, sleeves and trousers are all made from coconut fibre with human hair used for the decoration. The armour was generally in a good, stable condition, but covered in a layer of museum dirt. All three pieces were cleaned with brush vacuuming and then with groomstick (natural rubber). A small number of the human hair bindings on the cuirass required stabilisation, this was done using tinted Japanese tissue to secure the binding with a wheat starch paste: 4% methylcellulose 50:50 adhesive.

The trousers had a number of holes along the sides and one on the chest. These were secured with dyed nylon netting on the outside and the large hole on the side was also secured on the inside with dyed silk. This prevents the holes from increasing in size and also stops the mannequin from being visible through the hole while on display. Both the sleeves and trousers had deep creases along the edge from being stored flat. These were relaxed using local humidification with damp blotting paper and sympatex (a waterproof, water vapour-permeable membrane). Sympatex membrane brings the applied moisture in gaseous form to the surface of the object without the object actually coming into direct contact with the liquid.

Porcupine fish helmet Z 7035.

An impressive feature of the Kiribati armour is the helmet made from a hollowed out and dried porcupine fish. The helmet was created by hunting a porcupine fish while it is fully inflated and then burying it in the sand until it is dried out. The head is then removed and the skin is expanded in order to accommodate the head of the wearer. Ear guards were cut from the fish’s body.

Some helmets are composed of just the dried skin of the fish (like the MAA example), while some examples are reinforced with an internal coconut fibre helmet (see British Museum Oc1904,0621.28) and others are lined with plaited pandanus strips around the edges (see BM Oc1887,0201.54). The are several types of porcupine fish used, our helmet is from the Diodontidae family, most likely the Diodon hystrix as this was commonly used, however this cannot be confirmed for certain.

Before conservation

When the helmet arrived at the conservation lab it was unfortunately in a poor state. The ear guards were misshapen and bent inwards into the cavity of the helmet. They were both very dry and rigid, and each one had a tear along the bend. In addition there was also a number of broken barbs.

After conservation

The helmet was surface cleaned using a soft brush and conservation vacuum. This was done with incredible care as the surface of the skin was covered in sand, which could have been due to the manufacturing process, so I wanted to leave this in place. Luckily the sand was attached quite securely to the surface. The broken barbs were repaired using 20% Mowilith 50 (polyvinyl acetate) in 50:50 Industrial Denatured Alcohol: acetone, as this is a strong adhesive and tacky, but allows the retention of flexibility.

The main issue was the misshapen guards. There are a number of ways to reshape materials from localised humidification using sympatex sandwiches, to humidifying the whole object by creating a humidity chamber. As it was only the flaps that required reshaping I decided to use localised humidification using a preservation pencil connected to an ultrasonic humidifier. When this was complete I now had access to the reverse of the tears so was able to stabilise these by attaching a backing of Japanese tissue (Tosa tengujo) with 2% Methylcellulose in deionised water.

Now that the objects have been cleaned and stabilised, they are ready to be mounted for the exhibition. Due to the fragile nature of the materials this will take place next year just before the exhibition opens in April 2017. Thank you to the Pacific Presences team for providing me with the opportunity to research and work on such unusual and interesting objects.

Rachel Howie 2016

Posted on July 14, 2016 in Uncategorized

Pacific Presences Affiliated Researcher Areta Wilkinson writes on her most recent work for the project in Guam in May 2016:

Thank you to the Pacific Presences project for supporting my participation at Mo’na Our Pasts Before Us, 22nd Pacific Histories Association Conference in Guam, Mariana Islands. Over the last few years I have been fortunate to join Pacific Presences photographer Mark Adams and other project staff on research trips. As an Affiliated Researcher, the project has also supported my own artistic inquiry of taonga Māori (Māori customary objects) held in museum stores in England and Germany.

Mark Adams, Areta Wilkinson and Julie Adams in the dark room. Acknowledgements: Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin and Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde of Munich

In the dark room. Acknowledgements: Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin and Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde of Munich

Under the Pacific Presences project Mark and I have developed an ethical conceptual collaboration that is a marriage of both our creative practices and more. We have produced new artworks that respond to and acknowledge taonga Māori in museums abroad. This new body of work feels highly significant to us because we would not have produced this work on our own, it requires both our cultural genealogies (that relate to the object) in order to do so. Thus far we have only exhibited the resulting artworks in New Zealand, Pacific Presences staff knew what we were up to but had not seen the fruits of our (and their) labour. The 22nd PHA conference was a fantastic opportunity to share our contemporary artistic outcomes responding to Oceanic art and European museums with our own Pacific Presences crew as well as conference goers.

24.7.2015 Silver Bromide Photogram. Z6469 Cheviot Hill. Collections of Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge, UK. Silver bromide fibre based paper Areta Wilkinson and Mark Adams 2015

Presenting alongside Nicholas Thomas, Julie Adams, Ali Clark, Lucie Carreau, Alana Jelinek, Maia Nuku and others under the diverse Pacific Presences project umbrella was certainly a highlight. Papers spanned three sessions over which I caught up on our team’s research developments and objectives. I felt this was a concerted effort by MAA and associates to reach out to scholars working in the Pacific, prior to connecting with indigenous artists at the Pacific Arts Festival that followed. Community books of Oceanic collection material held at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge and in other museums in Europe and New Zealand were created for the purpose of connecting communities with objects. I am pleased to hear these booklets came into their own when researchers went on to visit villages in the islands of Kiribati, Kanaky, and the Solomons.

It has been several weeks now since PHA but two lasting impressions have stayed with me since leaving Guam. Firstly, I noticed and appreciated indigenous scholars placing themselves in their research. Their relationship or cultural position was not presumed but up front and implicated. Māori academic Linda Tuhiwai Smith has contributed to my critical thinking about this through her articulation of Māori methodologies. In Māori centred frameworks, Māori are positioned as the collective stakeholders of their own knowledge, Māori take an active role in knowledge production and who benefits (Tuhiwai Smith 1999). In a cross-cultural context indigenous research as Localised Critical Theory also benefits the indigenous community being researched (Denzin, Lincoln, & Tuhiwai Smith 2008, p. 9). Politically I have occupied myself with Kaupapa Māori principals (Māori Critical Theory) over the last few years, so I found it confusing at PHA when conference presenters did not disclose their methodology behind engaging with cultural knowledge that obviously was not their own. Papers that discussed a cultural form without revealing their relationships to the culture fell short for me. This sort of inquiry is not robust enough anymore.

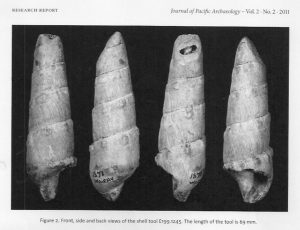

Secondly, I was made aware of my own short comings then had a Te Ao Marama “lights on” moment. In a discussion following panel presentations about Māori History, Vincente Diaz in his questioning of the panel seemed to remind our assembled collective to look for whakapapa connections beyond Polynesia, into Melanesia and Micronesia. To seek and find relationships is also a valued convention within our Māori rituals of encounter. As manuhiri, being a visitor, on the indigenous island Guahan I felt I could have improved on my own relating into the Pacific beyond Aotearoa New Zealand. I didn’t do this in my paper but during this session’s discussion a cog turned for me. Suddenly I had a better understanding of the presence of a photogram artwork that Mark and I had made, taken from a shell tool from the Pacific found in the site of Wairau Bar, Te Waipounamu South Island. Here was my mnemonic for Diaz’s message, my link to East Polynesia and beyond was under my nose all the time. But I had to be in a Pacific context, confronted by Pacific peoples to work it out.

The shell tool from Wairau Bar, E199.1245. Collection of Canterbury Museum, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Post PHA, Mark and I very recently accompanied Lucie Carreau with her whānau on her research trip to Norfolk Island. This time I was proactive to reach across into the Pacific to make connections. With the assistance of Norfolk Island Museum director Janelle Blucher Director and local artist Kerry Robertson we initiated an evening with locals to share our research interests. Face to face kanohi ki te kanohi it was a wonderful meet and greet opportunity that we all appreciated. Further contacts in the days remaining made it clear another trip would be warranted and we would all be welcomed back.

No reira, these research trips continue to have a positive impact on the development of my thinking and practice. Hei kona ma, na te ropū whakahaere, until we meet again.

Dr Areta Wilkinson, NZ (Ngāi Tahu)