Posted on April 3, 2018 in Solomon Islands, Uncategorized

In this blog entry Pacific Presences intern Hannah Eastham describes a short piece of work on the collection of Toshio Asaeda at the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka, Japan.

Having spent the last 2 years living in Osaka to develop a PhD project on the photographs of Japan from the James Hornell collection at the MAA, I was delighted to be given the opportunity to develop my experience in a different region by undertaking a Pacific Presences’ internship for the MAA at the National Museum of Ethnology in Japan (“Minpaku” as it is affectionately known). The Minpaku contains over 6,000 images taken during the expeditions of Charles Templeton Crocker, an American millionaire who financed the building of a luxury yacht, the Zaca, and began a series of scientific and anthropological research expeditions to the Pacific in the 1930s.

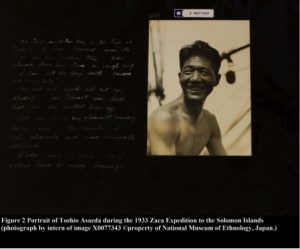

At the start of the work on January 26th, I was joined by researcher, Dr. Norio Niwa, and the Audio-Visual team at the Minpaku (Figure 1 above). They gave me an introduction to the material I was to review: a unique record of the Templeton Crocker expeditions made by Japanese photographer and artist, Toshio Asaeda (Figure 2). Toshio Asaeda, born in Tokyo in 1893, arrived in 1923 to the USA as an international exchange student. From 1925 to 1927, he began employment at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, accompanying the author, Zane Gray in travels to the South Pacific in 1931. From 1932 he became a regular member of Charles Templeton Crocker’s research expeditions, working as an artist, photographer and map-maker. His collection of photographs, diaries, and artwork were donated by the Asaeda family to the Minpaku museum in 1986.

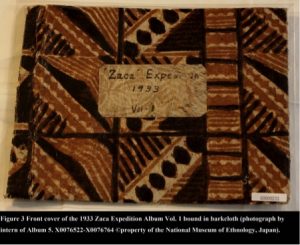

The focus of this internship was specifically to undertake a scoping exercise of the records at the Minpaku from the 1933 Scientific Expedition to the Solomon Islands, and the 1934-5 Scientific Expedition to South Pacific for the American Museum of Natural History. Before starting the work, I had previous contact with the collection through an internal database of digital photographs and inscriptions from the collection. However, this experience was entirely transformed when I was given access to the original images, which form part of a series of 16 photograph albums, hand-made and bound in materials (barkcloth for albums from the Pacific) sourced from the expedition by Asaeda (Figure 3 below).

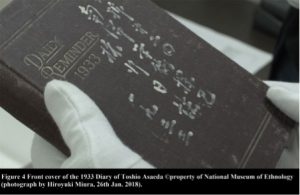

Having cast my eye over the diaries with Dr. Niwa at the beginning of the internship, it became clear that my Japanese skills would be nowhere near sufficient to translate the text, which was written mainly in a cryptic mix of Japanese characters with a few scattered English words resulting in a highly nuanced, diary short-hand, difficult to understand even for a native speaker of Japanese (Figure 4 above).

Whilst many of the photographs from this collection can also be found in the Templeton-Crocker collections at the MAA, it felt important to capture these images again in the format of these albums to understand the expeditions as told through Asaeda’s experience. It was decided, therefore, that the bulk of my time would be devoted to photographing and collecting data from Volumes 1, 2 & 3 from the Zaca 1933 Expedition, and Vol 1. & 2 from the 1934-5 Templeton Crocker Expedition. The images had been meticulously documented on the Minpaku’s database which considerably sped up the work. However, as each page of the albums is stored for conservation purposes in plastic film, I spent a week in the office experimenting with tripods, lighting, and multiple camera settings to try and avoid the glaring reflections from the shiny covers to capture the albums in as much detail as possible.

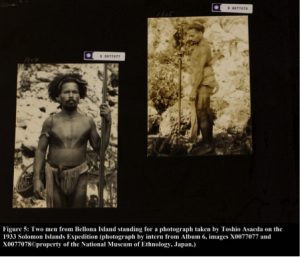

It was no easy task, but motivated by the beautiful work of Asaeda, and recognising the importance of capturing the record of these expeditions as experienced through this unpublished account, I was determined to get as many photographs as possible. In a short time, I was completely absorbed in the albums and took great pleasure in learning more about the geography of the Pacific and the diversity of its island cultures (such as, Bellona and Santa Catalina Island in the Solomon’s, Figure 5 & 6 below).

This collection is enriched by Asaeda’s artwork, a series of watercolours of marine sea creatures produced after the expeditions, and artistic impressions of his life from 1942-1945 when he was imprisoned in the USA at a Japanese internment camp. Experiencing this part of the collection, it was poignant to reflect on the life of an individual, who had collaborated with American peers, free to roam the seas, daring to undertake incredible voyages, risking his life on many occasions for the purposes of scientific research and museological collection, to then be confined and cut off from the world for many years.

It was a privilege to experience a collection which represents an important historical and artistic record by a Japanese photographer who has made a significant contribution to anthropology and photography, fields which in his day were dominated by Europeans and Americans. Not only is Asaeda’s work an exceptional legacy relevant to the history and cultures of the Pacific islands, but these incredible encounters are brought to life by a man who witnessed this world through a unique cross-cultural lens, using his creative and artistic abilities to record the history of the people and customs of the Pacific’s distinctive and diverse cultures.

Hannah Eastham, March 2018.

Posted on December 16, 2015 in Melanesia, Sepik River, Solomon Islands, West Papua

“Those people are constantly chewing a fruit which they call areca, and which resembles a pear. They cut that fruit into four parts, and then wrap it in the leaves of their tree which they call betre…They mix it with a little lime, and when they have chewed it thoroughly, spit it out. It makes the mouth exceedingly red. All the people in those parts of the world use it, for it is very cooling to the heart, and if they ceased to use it they would die” – Antonio Pigafetta (1521)

Following my introductory post, this piece will explore specific uses of the bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria). Within the Pacific, a great importance is placed on the bottle gourd for storing lime powder. This is visible in the collections of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge (MAA), which reflect the great geographical spread of such containers, having been collected from across Santa Cruz, the Bismarck Archipelago and the Solomon Islands, to name just a few places.

Historically, lime powder has been used by Pacific groups for its use in producing ‘betel’, as illustrated in the quote at the beginning of this post. Whilst its ability to prevent death is certainly questionable, this substance is one which can create powerful psychostimulating effects. The chewing of betel remains a popular practice within all aspects of Pacific life; courtship, death, peace-making, traditional medicine and ritual activity. It is frequently used across Melanesia, especially in New Guinea, New Britain and New Ireland. This is reflected in the material culture that was collected from these areas by colonial explorers during the late 19th-early 20th century, in particular a very high number of lime containers were collected. I will now introduce you to some specific examples of such containers, demonstrating the variety in form and decoration which can be seen within the MAA’s vast collection.

The first object (1927.1576) is a large, round gourd with no external decoration or patterning. It has a carved wooden spatula attached to its body by a string of sinnet material. This illustrates its use for combining lime powder with the areca palm fruit and betel pepper leaf. It was collected from the Massim District of Papua New Guinea, before being donated to the museum by Bernard Armitage (1890-1976), a physician and psychiatrist.

In contrast to the previous item, this lime box (Z 11227) is made of a gourd which has an elongated shape, manipulated to form its concave bottom. However, it displays a similarly plain exterior. It is from the Solomon Islands and was given to the museum by Baron Von Hügel in 1884; an explorer who was travelling in the Pacific between 1874 and 1877. What is especially intriguing about this object is the semi-human, semi-animal figure featured on the handle of its wooden stopper. This figure can be seen crouching on all fours, wearing a necklace of red and white glass beads around its neck. It is also wearing what appears to be a top hat, arguably depicting a Pacific representation of a European.

This gourd object (Z 1283) was collected by A.C. Haddon during his Torres Strait Expedition in 1898. It is from the Trobriand Islands. Unlike the previous items, its exterior features simple burnt designs. Where there is now a hole in the top of the item, a stopper would once have been placed in order to create a secure container for the lime powder it stored. It is worth drawing your attention to the damage which can be seen on the bottom of this vessel. This damage has created access to the interior material of the gourd, which can then be exploited for the sampling purposes I mentioned in my previous blog post. This minimises any risk of damaging a part of the object which is still intact.

I hope that you have enjoyed reading about these Pacific gourd containers. My next blog post will focus on MAA’s collection of Hawaiian gourds, a taster of which can be seen below!

Emily Wilkes

Posted on November 27, 2015 in Solomon Islands, Uncategorized

Over the past few months, project intern Emily Wilkes has been busy working with Pacific Presences team member Lucie, exploring the museum’s collections for Pacific objects made from gourd material, here is her first blog post on the project:

This work is being carried out with the Pacific Presences Project, in conjunction with Dr Andrew Clarke of the McDonald Institute, University of Cambridge. The aim of this collaborative project is to carry out DNA analysis on samples collected from gourd artefacts stored in the MAA. This will help fill critical research gaps relating to the origins, international spread and domestication of the bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria). At present, we know that the bottle gourd originated in Africa and had spread to South America by at least 9,900 years BP, but questions such as how it travelled to the Pacific, remain unanswered. This project will help researchers in their quest to reconstruct the global movement of this plant. It will contribute to our understanding of how groups within the Pacific selected for certain traits, determined by how they were used culturally. This domestication process will have influenced the evolution of specific gourd shapes and sizes and can be seen in the museum collection today. The results obtained from DNA analysis of Pacific objects will form the focus of a comparative framework for linking similar data collected from African and Asian gourd items.

As part of this project, I have been working on creating a shortlist of museum items which are suitable for sampling purposes. The MAA has a magnificent collection of over 200 Pacific objects made from gourd material, many of which were accumulated by early voyagers in the late 19th-early 20th century. They include items collected from across Polynesia, Melanesia and Micronesia. I have been looking through these assemblages, recording each object’s dimensions, form, use and suitability for sampling. Whilst the sampling process involves taking only a small scraping from the inside of the gourd, access to this interior material is sometimes completely blocked, for example, by wooden stoppers which we are unable to remove. The process aims to be as non-destructive as possible and the material will not be manipulated for testing purposes; only those objects already displaying openings wide enough to collect a sample will be used. Therefore, it is critical that information regarding an item’s suitability for sampling is thoroughly recorded. In addition to this, I have been photographing the collection, helping to improve the information available to those searching for items on the museum database. Being able to digitally view what a specific object looks like minimises the need to physically remove the artefact from the museum’s stores, therefore helping to conserve it for future generations.

Lime gourd from the Santa Cruz Islands. Collected by Reverend William Chamberlain o’Ferrall, Melanesian Mission, between 1897 and 1902, donated to the Museum in 1920. IDNO: 1920.734. Photo by Emily Wilkes, October 2015. © MAA.

Over the next few weeks, I will be writing about some of the fantastic items I have been recording. I will be introducing you to items ranging from intricately decorated water containers collected in Hawaii, to a bottle gourd on which some rather mysterious animal feet are mounted! The photo below is a taster of the first of these case studies. This will explore the use of the bottle gourd for storing lime within Pacific communities and will be posted very soon!

Emily Wilkes

Posted on August 7, 2014 in Micronesia, Solomon Islands

In February I visited the Pacific collections at the Powell-Cotton Museum, Quex Park in Birchington on Sea, Kent. The purpose of the visit was to get a general overview of the Pacific collections, which were in the process of being rediscovered and catalogued in a collections review by the newly appointed collections manager. The Powell-Cotton neither has a Pacific focus or an electronic catalogue so the visit was something of a treasure hunt.

The Powell-Cotton Museum at Quex Park in Kent houses the natural history and ethnographic collections of Major Percy Horace Gordon Powell-Cotton. Powell-Cotton collected from all over the world but predominately Africa. In 1981 the collections of the Powell-Cotton were assessed by Keith Nicklin for the Museum Ethnographers Group newsletter. He noted that the development of the museum can be understood in three distinct phases; the first as the founding of the museum and the development of its field based collections, the second as the development of the museum itself and cataloguing and filling gaps in the collection, and the third occupied by Nicklin and his article in the 1980s and onwards as the analysis and publication of the collections. The development of the Pacific collections occurred during this second phase. Between 1936-1938, sensing a gap in his collections, Powell-Cotton bought up several collections from the Pacific. His Pacific collections were purchased in six lots from auction houses and local amateur collectors. One of these collections was comprised of 103 objects from the Davis collection and it is this collection that drew my interest.

Edward Henry Meggs Davis commanded the Australian station third class cruiser, H.M.S Royalist, between 1890 and 1893. He sailed around the western Pacific, stopping at the Solomon Islands, Fiji, the Marshall Islands, Tuvalu (Ellice Islands), Kiribati (Gilbert Islands), Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea and New Caledonia. The voyage was divided into several trips over the course of three years, with Davis originally working in Vanuatu and New Caledonia in 1890. In 1891 he was then instructed to establish law and order in the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea after the deaths of several European traders in the region, and spent a approximately a year there. Davis then sailed around Kiribati and Tuvalu declaring British protectorates amongst the Islands. The Davis collection was made during these assignments and objects were collected from the Islands he worked in, as well as in the Islands the ship passed on its way back and forth to Australia where the ship was stationed.

Davis returned to his home in Bexhill, Sussex in 1894, commissioning a local printer to publish a catalogue of his Pacific collection of just over seven hundred objects. Originally intending to sell the collection to a friend – who later declined to make the purchase – Davis found himself tasked with selling the collection in order to fund his retirement. He chose the firm Gerrard and Sons, a London based taxidermist and dealer, to sell the collection on his behalf. Gerrard and Sons was set up by Edward Gerrard in 1850 and run by his sons and brother as a taxidermists and furriers, remaining a family firm until its closure in 1967. Edward Gerrard had set up the firm in whilst employed in the Zoology department at the British Museum, continuing to work at the British Museum and hiring his son to run the new business. The sale of the Davis collection drew on both Gerrard and Sons’ and Davis’ networks of private collectors, and museum curators within the UK and Europe. Parts of the collection were purchased by private collectors James Edge-Partington, Harry Beasley and J F G Umlauff, and museums including the British Museum, Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum, and the Powell-Cotton. Currently the collection can be found in the Powell-Cotton, the Pitt-Rivers, the Horniman, the British Museum, MAA Cambridge, Liverpool World Museum, National Museums Scotland, Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum, Otago Museum and Auckland Museum.

The initial visit in February to the Powell-Cotton has led to me attempting to track the dispersal of the Davis collection; photographing, cataloguing and hopefully exhibiting the various parts in their various locations. This blog entry discusses a few objects from the Davis collection and the visits I have made to the museums who act as custodians for this dispersed collection.

The focus of the Powell-Cotton Davis collection appears to be body adornment, and their collection is rich in these type of objects particularly from Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. 80% of the Davis objects purchased for the Powell-Cotton are made of animal parts fitting with Powell-Cotton’s interest in the natural world such as D73/1938, two polished sperm whale teeth from the Solomon Islands, hung on a plaited coconut fibre cord. Davis describes these objects as having been worn around the neck and would have been worn as valuables alongside other neck ornaments such as D63/1938, two clam shell neck ornaments that are missing their cords. In an article on whales teeth ornaments, Rhys Richards writes that Davis was collecting these valuables during ‘his punitive raids ‘to stamp out headhunting’ from coastal villages around Roviana Lagoon and at Munda’ (Richards 2006:11). Unusually the Richards article reveals research conducted at the Powell-Cotton highlighting their collection of Davis whales teeth and arguing that D73/1938 ‘is particularly interesting in having two pairs of tiny holes centrally placed…but also a single large hole at the gum end (seemingly made by a metal drill), so that it could have been hung horizontally or worn vertically’ (Richards 2006:11). The whales teeth at the Powell-Cotton are by no means ‘star’ objects, but what makes them more interesting is their ability, alongside other pieces of body adornment in the collection, and other items such as shell fish hooks, to demonstrate how people used their environment, and the social life and material culture of the region, as well as what was perceived as valuable or interesting by Davis.

Subsequent research into the Davis collection revealed a rich archive of documents relating to the movements of the ship and Davis’ work in the Pacific, housed at the National Library of Australia, the Australian Maritime Museum and the National Archives at Kew. Research conducted in Australia in April also revealed a photo collection taken during the cruise of the Royalist by an unknown photographer. Copy collections are held at the Macleay Museum, Sydney and the British Museum, with the original album held at the Fiji Museum. Through these photographs we gather glimpses of the material culture being used, or worn by the people Davis often brought onto the ship. Further research needs to be done on these photographs but through them and the archives we can begin to contextualize the practice of collecting.

The next collections visit was to the British Museum, who have 141 objects from the Davis collection, 67 purchased via the Christy Collection, 41 purchased directly from Gerrard and Sons and 33 donated by the collector Harry Beasley. The British Museum were given first pick from the collection and chose many of the ‘masterpiece objects’ one of which is an incredibly intricate cuirass from Kiribati (Oc1904,0621.29). The armour is made from plaited lengths of coconut fibre placed on top of one another. Each one is then covered with two ply twisted coconut fibre cords and are secured in place by interlinking cord. The sides of cuirass have a waistband and the back has a knot of coconut fibre cord with human hair protruding from it. A panel of porcupine ray skin is fixed to the front and right side of the torso with coconut fibre. The head guard is decorated with two black lozenges of human hair, thought to represent dolphins with bands of hair as edging. Described in the Davis catalogue as no.495 ‘Sennet armour, breast covered fish skin, and helmet of fish skin. Gilbert Islands’. I believe the helmet he refers to to be Oc1904,0621.28. Based on reading the ships logs, held at the National Archives these two objects would have been collected between the 24th of May 1892 and the 30th of July 1892. This armor is also depicted in one of the photographs held at the Fiji Museum. There are two holes mid way down the front of the porcupine ray skin, and some damage in a patch further down to the left with one large perforation near the base of the cuirass perhaps made by weaponry; this same hole can be seen in the photograph.

Finally a few weeks ago I visited the Pacific collections at the Horniman. The Horniman has sixty-four objects from the Davis collection, two donated by Beasley, the rest purchased from Gerrard and Sons. Davis collected a variety of objects associated with life in the Pacific such as body adornment, clothing, fishing equipment, bags, weapons, musical instruments and tools. Many objects within his collection are associated with everyday life, however Davis also collected some ‘masterpiece’ objects, often described as ‘rare’ in his catalogue. Most of these are now in the British Museum, however some of these eye catching pieces are within the Horniman collection and include two beautifully carved fish hooks (30.49, 30.53), and one Kiribati body belt (30.40) made from porcupine ray skin that would have been worn with the armour described above.

The two bonito fish hooks from the Solomon Islands would have been used for fishing without bait, as the iridescent mother-of-pearl colour and the ‘glittering of the shank when moving, looked like little live fishes which the bonito tried to snap at’ (Mosher 1955: 186). What is different about these two fish hooks is that the shank of one (30.49) has been purposely carved out of pearl shell to resemble a bonito fish, whilst the other (30.53) has a fish carved from pearl shell wrapped onto the tortoise shell shank with coconut fibre binding. Through reference to their utilitarian purpose these objects become visually stunning. These objects also demonstrate the reliance on the sea for Solomon Islands society, as whilst being used for fishing they are also made of materials from the sea; turtle shell and pearl shell.

The belt is formed from two pieces of porcupine ray skin sewn together with human hair and coconut fibre cord. The ends of the skin are sewn onto wooden poles, which have been wrapped in hair and coconut fibre. A two-ply twisted coconut fibre cord is attached to these poles possibly to enable the wearer to pull the belt tighter. Described in the Davis catalogue as ‘498 Body belt of ray skin, very rare’ this belt would have been worn as armour, over a coconut fibre cuirass, accompanied by coconut fibre arm and leg coverings and a fish skin helmet. In his notes from Kiribati Davis writes that the Gilberts people have ‘sharks teeth spears and swords, also complete suits of armour made of rope from the coconut fibre. Occasionally fighting belts are worn over these made from the skin of the stingray’ (Davis The Proceedings of the HMS Royalist 1892). Pacific Presences is also currently conducting a survey of coconut fibre armour in UK museum collections. Initial research has demonstrated that coconut fibre armour is relatively common amongst museum collections from Kiribati, but these porcupine ray skin belts are much less common with only a few in the UK and Europe.

Collections’ such as Davis’ are complex relational assemblages and when looking at the Horniman’s Davis collection I can begin to see Davis’ large collection reform as similar objects begin to pop up and the collecting patterns of curators and collectors begin to emerge. A final example of this are the objects described by Davis as ‘Ingenious flying fish hook line and float, Onotoa, Gilbert Islands’. These objects are 606-609, 612 and 624 in his catalogue and are found in the British Museum (Oc1894,-.225-227 and Oc1980,Q.946), Horniman (30.37) and Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge (E 1904.47). Each float bears the handwritten inscription ‘Flying Fish Line, Onoatoa, Gilbert Ids’, most probably made by Davis, and the MAA object even has the Davis catalogue number 608 written next to this inscription. Whilst the objects were all provenanced to Davis in some way, the MAA object was not listed on the collections database as being collected Davis. It was through recognising the handwriting and the inscription from those objects in the British Museum and the Horniman that correct attribution could be given on the online database.

The Horniman was the fifth museum to hold objects from the Davis collection that I have visited, and I have two more to visit in the UK over the coming months. By visiting these many museums begins to expose the ways in which museums and collectors in the UK and mainland Europe were engaging with the Pacific, and how these collections were being formed.

Ali Clark