Traces of the H.M.S Royalist in Vanuatu

Posted on September 4, 2017 in Uncategorized

Eve Haddow, a PhD candidate at the Australian National University has been working as an intern for Pacific Presences, recently her research took her to Vanuatu. In this blog post she describes her research and its exciting findings:

Readers of the Pacific Presences blog may be familiar with the collection of Admiral Edward Henry Meggs Davis, which Research Associate Dr Ali Clark has been investigating in detail. The collection of 1446 ethnographic artefacts from the Western Pacific was acquired while Davis was in command of the H.M.S. Royalist, 1890-93. As a Pacific Presences intern I have been exploring the material Davis acquired from Vanuatu (462 items). I recently returned from fieldwork in Vanuatu, where I hoped to find out if there were any contemporary ni-Vanuatu perspectives on the collection, and on the historical activities of H.M.S. Royalist.

The Royalist travelled through Vanuatu for just over 6 months in 1890. At that time, Europeans collectively called the islands the New Hebrides/Nouvelles Hébrides, as named by Captain Cook. Davis and his crew were tasked with maintaining a British naval presence in the area, often responding to incidents with force – it is no coincidence that ships such as the Royalist were commonly referred to as a ‘man-of-war’. Davis intervened in a number of disagreements between ni-Vanuatu and traders living in the region, as well as disputes involving recruiters engaging people in indentured labour for plantations in Queensland, New Caledonia, Fiji and elsewhere in Vanuatu.

When I first looked at the list of items that Davis collected in Vanuatu, two things struck me. First was the sheer number of bows and arrows he collected (25 bows and a whopping 300 arrows!). Reading naval reports from the time, it seems likely these items are connected with Davis’ confiscation of weapons. Second, was the association of one artefact with a named individual (Fig. 1). In Davis’ catalogue of his collection, he lists a ‘pig hammer of TAPPEA’, with a note: ‘chief of Aure ID New Hebrides’. This is noteworthy as only three original owners are named within the entire catalogue. I wondered who Tappea was, and what had happened to make Davis record his name?

‘Aure’ and ‘Aura’ are 19th-century names for the 58km² island of Aore, situated on the south coast of Vanuatu’s biggest island, Espiritu Santo. Aore is a short boat trip across the Segond Channel from Luganville, the largest town on Santo and second largest in Vanuatu with a population of around 12,000. Today, as in 1890, a much of Aore is home to coconut plantations. There is also a coffee plantation, Aore Academy (a Seventh Day Adventist secondary school), and several expensive holiday resorts. Figures compiled in 2010 indicate 65.3% of Aore was leased (Scott et al. 2012: 3). This is an extraordinarily large amount of alienated land when compared with other islands in Vanuatu. When I arrived in Luganville, I was repeatedly told there is ‘no man Aore’. Many claim the last of the local population was forced to leave the island sometime in the early 20th century, as people were being poisoned by a European plantation owner.

On Aore, I met Chief Takau Muele, one of the current Chiefs of Aore, Malo, Tutuba and Mavea islands (Fig.2). He and his parents were born on nearby Malo, but have ancestral connections to Aore, making him a traditional landowner. Chief Takau has a great knowledge of the culture and history of the area. Sitting in his house on Aore, I showed him an image of Tappea’s club. Chief smiled, and asked his daughter Joyce to reach under his seat for his own club, which was a very similar style to Tappea’s (Fig. 3). He told me that in his Malo language it is a wawusa, made of wood of the aru tree, and associated with pig killing ceremonies.

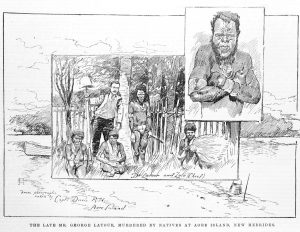

Chief Takau’s late father told him the story of a man named Tartappea of Aore, who had been taken by white men on a ship to Noumea. Newspaper reports of the time say Tappea was sentenced to 15 years hard labour by the French government for murdering the crew of the ship Idaho, and Chief Takau told me Tartappea never returned to Aore. Through oral and archival sources, I’ve been able to unravel the tangled web of events on Aore in 1890. Tappea was picked up by Davis following the complaints of a plantation owner named George De Lautour. This Englishman, who settled on Aore in 1885, was embroiled in local politics and often involved himself in disputes with islanders, planters, recruiters, and missionaries alike. A diary kept by Lautour for the year 1887, held at the National Museum of Fiji, gives a glimpse of Lautour’s bad-tempered nature. In April 1890, Lautour informed Davis that two men, Tappea and Thor, had kidnapped his ‘housekeeper’. Davis investigated the matter, and it was he who sent Tappea to Noumea for trial. In September 1890, a report reached Davis that Lautour and his 19-year-old son were dead, apparently murdered by Thor and some men from Malo. Thor claimed his actions were retribution for Lautour’s murder of two people on Aore, and for destroying Thor’s possessions and banishing him from the island.

The Royalist returned to conduct an investigation. After a short time gathering statements, with the Presbyterian missionary on Malo acting as interpreter, Davis found Thor and two men from Malo guilty, and sentenced them to death. In a show of colonial power, Davis had the men executed by firing squad. Chief Takau Muele’s father told him a story of four males from Malo who were involved in the incident, two he described as boys. The events were reported in the Australian press, with an obvious bias towards Lautour.

The details are shocking, with reports of 80 British naval officers landing on Aore for the execution, and other papers erroneously reporting that Lautour’s son was eaten, despite all official records contradicting this. Davis received criticism from the Western Pacific High Commissioner for his violent actions, and his misplaced involvement in what the Commissioner deemed a ‘domestic dispute’.

What has emerged from my research of Tappea’s club is a story of murder, injustice, colonial violence, politics and land, the traces of which are present in Vanuatu today. It is one of few artefacts I’ve been able to identify in museums as from Aore. After being told in Vanuatu there is ‘no man Aore’, the club now seems a rare material connection to Aore’s past. Tappea’s club might seem as symbolic of loss and colonial violence, if we consider the events of 1890 and the decades that followed, culminating in this claim of ‘no man Aore’ and the land alienation of over 60% of the island. But it is simultaneously a tangible link to the rich cultural history of Aore and surrounding islands, and provides a platform for exploring multiple aspects of this history with it’s echoes in contemporary Vanuatu.

I am currently writing this research into a chapter for Dr Clark’s forthcoming publication on the Admiral Davis’ collection. This will, I hope, be a chance to delve deeper into some of the emerging themes and to share more of this complex story.

Eve Haddow 2017