Posted on April 3, 2018 in Solomon Islands, Uncategorized

In this blog entry Pacific Presences intern Hannah Eastham describes a short piece of work on the collection of Toshio Asaeda at the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka, Japan.

Having spent the last 2 years living in Osaka to develop a PhD project on the photographs of Japan from the James Hornell collection at the MAA, I was delighted to be given the opportunity to develop my experience in a different region by undertaking a Pacific Presences’ internship for the MAA at the National Museum of Ethnology in Japan (“Minpaku” as it is affectionately known). The Minpaku contains over 6,000 images taken during the expeditions of Charles Templeton Crocker, an American millionaire who financed the building of a luxury yacht, the Zaca, and began a series of scientific and anthropological research expeditions to the Pacific in the 1930s.

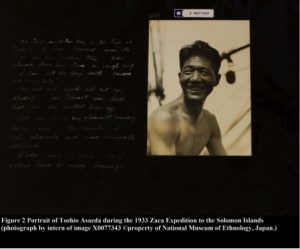

At the start of the work on January 26th, I was joined by researcher, Dr. Norio Niwa, and the Audio-Visual team at the Minpaku (Figure 1 above). They gave me an introduction to the material I was to review: a unique record of the Templeton Crocker expeditions made by Japanese photographer and artist, Toshio Asaeda (Figure 2). Toshio Asaeda, born in Tokyo in 1893, arrived in 1923 to the USA as an international exchange student. From 1925 to 1927, he began employment at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, accompanying the author, Zane Gray in travels to the South Pacific in 1931. From 1932 he became a regular member of Charles Templeton Crocker’s research expeditions, working as an artist, photographer and map-maker. His collection of photographs, diaries, and artwork were donated by the Asaeda family to the Minpaku museum in 1986.

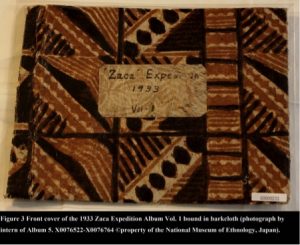

The focus of this internship was specifically to undertake a scoping exercise of the records at the Minpaku from the 1933 Scientific Expedition to the Solomon Islands, and the 1934-5 Scientific Expedition to South Pacific for the American Museum of Natural History. Before starting the work, I had previous contact with the collection through an internal database of digital photographs and inscriptions from the collection. However, this experience was entirely transformed when I was given access to the original images, which form part of a series of 16 photograph albums, hand-made and bound in materials (barkcloth for albums from the Pacific) sourced from the expedition by Asaeda (Figure 3 below).

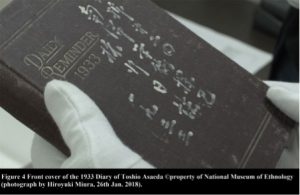

Having cast my eye over the diaries with Dr. Niwa at the beginning of the internship, it became clear that my Japanese skills would be nowhere near sufficient to translate the text, which was written mainly in a cryptic mix of Japanese characters with a few scattered English words resulting in a highly nuanced, diary short-hand, difficult to understand even for a native speaker of Japanese (Figure 4 above).

Whilst many of the photographs from this collection can also be found in the Templeton-Crocker collections at the MAA, it felt important to capture these images again in the format of these albums to understand the expeditions as told through Asaeda’s experience. It was decided, therefore, that the bulk of my time would be devoted to photographing and collecting data from Volumes 1, 2 & 3 from the Zaca 1933 Expedition, and Vol 1. & 2 from the 1934-5 Templeton Crocker Expedition. The images had been meticulously documented on the Minpaku’s database which considerably sped up the work. However, as each page of the albums is stored for conservation purposes in plastic film, I spent a week in the office experimenting with tripods, lighting, and multiple camera settings to try and avoid the glaring reflections from the shiny covers to capture the albums in as much detail as possible.

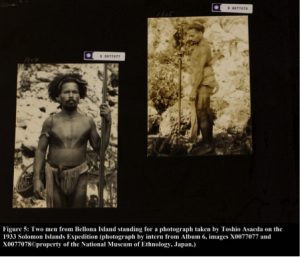

It was no easy task, but motivated by the beautiful work of Asaeda, and recognising the importance of capturing the record of these expeditions as experienced through this unpublished account, I was determined to get as many photographs as possible. In a short time, I was completely absorbed in the albums and took great pleasure in learning more about the geography of the Pacific and the diversity of its island cultures (such as, Bellona and Santa Catalina Island in the Solomon’s, Figure 5 & 6 below).

This collection is enriched by Asaeda’s artwork, a series of watercolours of marine sea creatures produced after the expeditions, and artistic impressions of his life from 1942-1945 when he was imprisoned in the USA at a Japanese internment camp. Experiencing this part of the collection, it was poignant to reflect on the life of an individual, who had collaborated with American peers, free to roam the seas, daring to undertake incredible voyages, risking his life on many occasions for the purposes of scientific research and museological collection, to then be confined and cut off from the world for many years.

It was a privilege to experience a collection which represents an important historical and artistic record by a Japanese photographer who has made a significant contribution to anthropology and photography, fields which in his day were dominated by Europeans and Americans. Not only is Asaeda’s work an exceptional legacy relevant to the history and cultures of the Pacific islands, but these incredible encounters are brought to life by a man who witnessed this world through a unique cross-cultural lens, using his creative and artistic abilities to record the history of the people and customs of the Pacific’s distinctive and diverse cultures.

Hannah Eastham, March 2018.